Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

"Bombay High Court Demands Retrial After Uncovering Major Fair Trial Violations and Procedural Lapses"

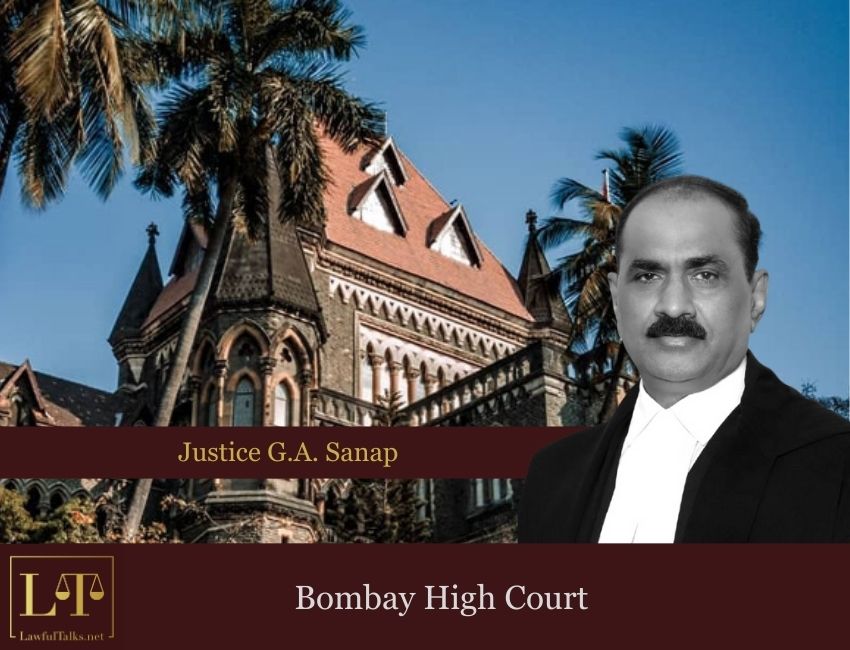

In a recent judgement, Justice G.A. Sanap of the Bombay High Court at Nagpur Bench examined serious procedural lapses in a criminal case, leading to an order for retrial. The appellants had been convicted of severe offences under sections of the Indian Penal Code, but procedural irregularities during the trial led the High Court to question the fairness of the original proceedings.

In this case, the appellants were convicted under multiple sections of the Indian Penal Code, including Section 452 for house trespass, Section 324 for voluntarily causing hurt by dangerous weapons, Section 366 for kidnapping or inducing a woman to compel her marriage, and Section 376(D) for gang rape, read with Section 34, which addresses acts done by several persons in furtherance of a common intention. According to the prosecution, on April 5, 2016, the accused, armed with sickles, allegedly broke into the victim’s residence and assaulted both her and her husband. The accused reportedly forced the husband to flee, after which they allegedly raped the victim. Following the assault, they transported her by motorcycle to several locations, including a petrol station where she was able to report the incident, setting off the investigation that led to the appellants’ conviction.

The Bench raised substantial concerns about the trial court's failure to comply with Section 273 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), which mandates that evidence be recorded in the presence of the accused. In this case, photographs were shown to the victim to identify the accused rather than requiring their physical presence in the courtroom. The Bench emphasised that such a deviation from the prescribed procedure undermines the foundational principles of a fair trial, stating, “All principles of fair trial had been thrown to the wind by the Presiding Officer as well as by the Prosecutor.”

Another significant issue was the prolonged duration of the trial. Section 309 of the CrPC requires that trials, particularly those involving serious offences, proceed on a day-to-day basis. Despite this mandate, the trial extended over two years to record testimonies from only ten witnesses. The Bench observed that this delay violated both the CrPC and the constitutional right to a speedy trial under Article 21, a right enshrined by the Supreme Court in Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar [AIR 1979 SC 1369], where the Court ruled that a speedy trial is a vital component of fair justice.

The Bench’s ruling emphasised that judicial officers must play an active role in trials, particularly in ensuring compliance with procedural standards. Citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Rahul v. State of Delhi, Ministry of Home Affairs and Another [(2023) 1 SCC 83] where it is observed that “A Judge is expected to actively participate in the trial, elicit necessary materials from witnesses in the appropriate context which he feels necessary for reaching the correct conclusion.” The Bench noted that judges are not mere bystanders but are expected to actively engage with trial proceedings to ensure both procedural compliance and clarity of evidence.

In this case, the trial judge failed to secure the physical presence of the accused for the victim’s identification, a lapse that could have been avoided through the use of video conferencing if in-person attendance was not feasible. The judgement also observed the presiding judge’s failure to employ all available measures to maintain procedural integrity, which in turn affected the reliability of the identification process.

The Bench also highlighted prosecutorial responsibilities, especially regarding the presentation of scientific evidence. The DNA report, a pivotal piece of evidence connecting the accused to the crime, was incomplete in court records, with only two of its four pages submitted. The Bench described this oversight as “shocking,” stressing that such omissions compromise the trial’s fairness. This lapse, combined with the absence of critical witnesses, such as forensic experts and custodians of evidence, weakened the prosecution’s case and emphasised the need for greater prosecutorial diligence.

The Bench stressed that prosecutors are responsible for ensuring all material evidence, such as DNA reports, is complete and verified under Section 293 of the CrPC, which allows scientific reports to be admitted with the necessary procedural safeguards. Proper examination of experts, particularly in cases involving scientific evidence, is essential to preserve the trial’s integrity.

The Bench highlighted major deficiencies in the examination of the accused under Section 313 of the CrPC, which allows the accused to respond to incriminating evidence. The questions posed to the accused were broadly framed, depriving them of the opportunity to address specific allegations. The Bench remarked, “The material part of the incriminating evidence adduced by the prosecution was not put to the appellants.” thus limiting the accused’s ability to mount an effective defencere.

Referring to the precedent in Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra [AIR 1984 SC 1622], the Bench emphasised the procedural obligation to clearly present all relevant evidence to the accused during their examination under Section 313. The Supreme Court has consistently held that failure to present specific questions on incriminating evidence renders that evidence inadmissible for establishing guilt. This ruling reinforces the judiciary’s duty to ensure accused individuals are fully informed of allegations and given the chance to respond.

In light of these extensive procedural shortcomings, the High Court ordered a retrial under Section 386(b)(i) of the CrPC. It was noted that a retrial does not imply any judgement on the guilt or innocence of the accused but is instead necessary to uphold legal standards and procedural integrity. He stated, “The informant/prosecutrix deserves a fair trial and justice. Similarly, the appellants also deserve a fair trial,” accentuating the judiciary’s commitment to impartiality and the right to fair proceedings for both the victim and the accused.

Case Details- Puranlal Sakaru Dhurve v. The State of Maharashtra [Cri.Appeal 155/2022]

Advocate for the Appellant- Mr. R.R. Vyas

Advocate for the Respondents- Ms. S.V. Kolhe, APP

(For more updates, tap to join us on Whatsapp, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn)