Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

The Supreme Court, while hearing a Public Interest Litigation under Article 32 of the Constitution, which raised an issue to address the failure of authorities to prevent child marriages despite it being debated in India for over one and a half centuries. The court has rejected the center's plea to enforce the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA) over personal laws and encourages Parliament to consider a ban on child betrothal.

The court observed that the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006, is a social legislation which requires a collective effort of all stakeholders for its success, emphasizing the need for community-driven strategies and more focus on prevention than prosecution.

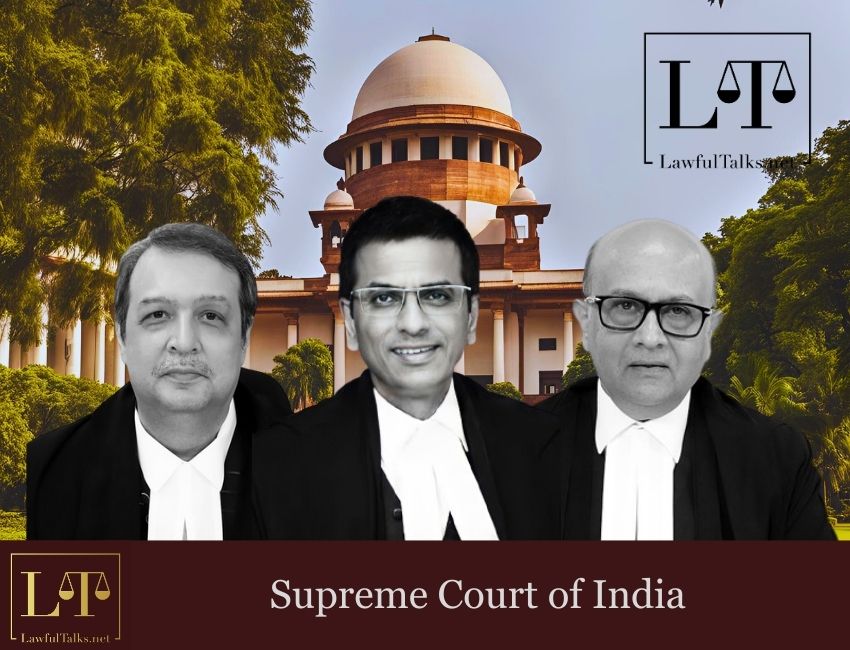

The bench, comprising Chief Justice of India Dr. DY Chandrachud, Justice J.B. Pardiwala,and Justice Manoj Misra, upheld earlier precedents of Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union, and others, where the Court had consistently affirmed India’s obligation with regards to international conventions and norms when interpreting domestic laws, and the court itself had established guidelines and followed a similar approach in this case as well and laid down a set of guidelines for the effective and useful implementation of the PCMA, which were stated ''to prioritise prevention before protection and protection before penalisation.''

''We are cognizant of the impact that criminalisation has on families and communities. To ensure effective use of penal provisions in the PCMA, it is imperative that there is widespread awareness and education about child marriage and the legal consequences of its commission.''

The Court, however, clarified that its stance should not be interpreted as discouraging the prosecution of individuals involved in illegal activities. "However, the aim of the law enforcement machinery must not be solely focused on increasing prosecutions without making the best efforts to prevent and prohibit child marriage. The focus on penalisation reflects a harms- based approach which waits for a harm to occur before taking any steps. This approach has proven to be ineffective at bringing about social change," the Court stated.

The Court noted that, ''Preventive strategies should therefore be tailored to the unique needs of various communities and focus on addressing the root causes of child marriage, such as poverty, gender inequality, lack of education, and entrenched cultural practices.''

The Bench observed that, India has yet to fully address the issue of child marriages, despite the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) highlighting the problem as far back as 1977. The court also in their exhaustive judgement recorded the landmark case of Rukhmabai (1874), which challenged traditional customs of child marriage and women's rights, and where Justice Pinhey's bold decision on declaration of the rights of Indian women to make their own life choices, which was considered ahead of its time, yet the issue of child marriage still prevails.

The judgment was based on petitions filed by NGOs, such as the Society for Enlightenment and Voluntary Action, which highlighted the alarming rate of child marriages despite the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA) being in effect for nearly two decades. The Supreme Court noted that the long-standing practice of child marriage in India posed a threat to contemporary laws, including the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO).

The court crucially pointed out that ''while the PCMA seeks to prohibit child marriages, it does not stipulate on betrothals. Marriages fixed in the minority of a child also have the effect of violating their rights to free choice, autonomy, agency and childhood. It takes away from them their choice of partner and life paths before they mature and form the ability to assert their agency. International law such as CEDAW stipulates against betrothals of minors. Parliament may consider outlawing child betrothals which may be used to evade penalty under the PCMA. While a betrothed child may be protected as a child in need of care and protection under the JJ Act, the practice also requires targeted remedies for its elimination.''

The Court directed that a copy of the judgment be transmitted to the Secretaries of all concerned Ministries, the Government of India which includes the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Ministry of Rural Development, statutory authorities, institutions, and organizations under the control of the respective ministries.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development was directed to circulate this judgment to the Chief Secretaries/Administrators of all the States and Union Territories, as well as NALSA, and NCCPR for strict compliance with the directions.

Case Title: Society for Enlightenment and Voluntary Action & Anr. V Union of India & Ors.

Advocate for Petitioner: Advocate Mugdha & ors

Advocate for Respondents: Advocate Gurmeet Singh Makker, Advocate Anando Mukherjee & ors

Akshaj Joshi

Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 352 Posts

- High Courts 366 Posts

SC Issues Guidelines & Asks Parliament To Consider Ban On Child Betrothals

- Akshaj Joshi

- October 21, 2024

PCMA States Nothing On The Validity Of The Marriage: SC Issues Guidelines & Asks Parliament To Consider Ban On Child Betrothals

The Supreme Court, while hearing a Public Interest Litigation under Article 32 of the Constitution, which raised an issue to address the failure of authorities to prevent child marriages despite it being debated in India for over one and a half centuries. The court has rejected the center's plea to enforce the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PMCA) over personal laws and encourages Parliament to consider a ban on child betrothal.

The court observed that the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006, is a social legislation which requires a collective effort of all stakeholders for its success, emphasizing the need for community-driven strategies and more focus on prevention than prosecution.

The bench, comprising Chief Justice of India Dr. DY Chandrachud, Justice J.B. Pardiwala,and Justice Manoj Misra, upheld earlier precedents of Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union, and others, where the Court had consistently affirmed India’s obligation with regards to international conventions and norms when interpreting domestic laws, and the court itself had established guidelines and followed a similar approach in this case as well and laid down a set of guidelines for the effective and useful implementation of the PCMA, which were stated ''to prioritise prevention before protection and protection before penalisation.''

''We are cognizant of the impact that criminalisation has on families and communities. To ensure effective use of penal provisions in the PCMA, it is imperative that there is widespread awareness and education about child marriage and the legal consequences of its commission.''

The Court, however, clarified that its stance should not be interpreted as discouraging the prosecution of individuals involved in illegal activities. "However, the aim of the law enforcement machinery must not be solely focused on increasing prosecutions without making the best efforts to prevent and prohibit child marriage. The focus on penalisation reflects a harms- based approach which waits for a harm to occur before taking any steps. This approach has proven to be ineffective at bringing about social change," the Court stated.

The Court noted that, ''Preventive strategies should therefore be tailored to the unique needs of various communities and focus on addressing the root causes of child marriage, such as poverty, gender inequality, lack of education, and entrenched cultural practices.''

The Bench observed that, India has yet to fully address the issue of child marriages, despite the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) highlighting the problem as far back as 1977. The court also in their exhaustive judgement recorded the landmark case of Rukhmabai (1874), which challenged traditional customs of child marriage and women's rights, and where Justice Pinhey's bold decision on declaration of the rights of Indian women to make their own life choices, which was considered ahead of its time, yet the issue of child marriage still prevails.

The judgment was based on petitions filed by NGOs, such as the Society for Enlightenment and Voluntary Action, which highlighted the alarming rate of child marriages despite the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA) being in effect for nearly two decades. The Supreme Court noted that the long-standing practice of child marriage in India posed a threat to contemporary laws, including the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO).

The court crucially pointed out that ''while the PCMA seeks to prohibit child marriages, it does not stipulate on betrothals. Marriages fixed in the minority of a child also have the effect of violating their rights to free choice, autonomy, agency and childhood. It takes away from them their choice of partner and life paths before they mature and form the ability to assert their agency. International law such as CEDAW stipulates against betrothals of minors. Parliament may consider outlawing child betrothals which may be used to evade penalty under the PCMA. While a betrothed child may be protected as a child in need of care and protection under the JJ Act, the practice also requires targeted remedies for its elimination.''

The Court directed that a copy of the judgment be transmitted to the Secretaries of all concerned Ministries, the Government of India which includes the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Ministry of Rural Development, statutory authorities, institutions, and organizations under the control of the respective ministries.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development was directed to circulate this judgment to the Chief Secretaries/Administrators of all the States and Union Territories, as well as NALSA, and NCCPR for strict compliance with the directions.

Case Title: Society for Enlightenment and Voluntary Action & Anr. V Union of India & Ors.

Advocate for Petitioner: Advocate Mugdha & ors

Advocate for Respondents: Advocate Gurmeet Singh Makker, Advocate Anando Mukherjee & ors

Akshaj Joshi

Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 352 Posts

- High Courts 366 Posts