Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

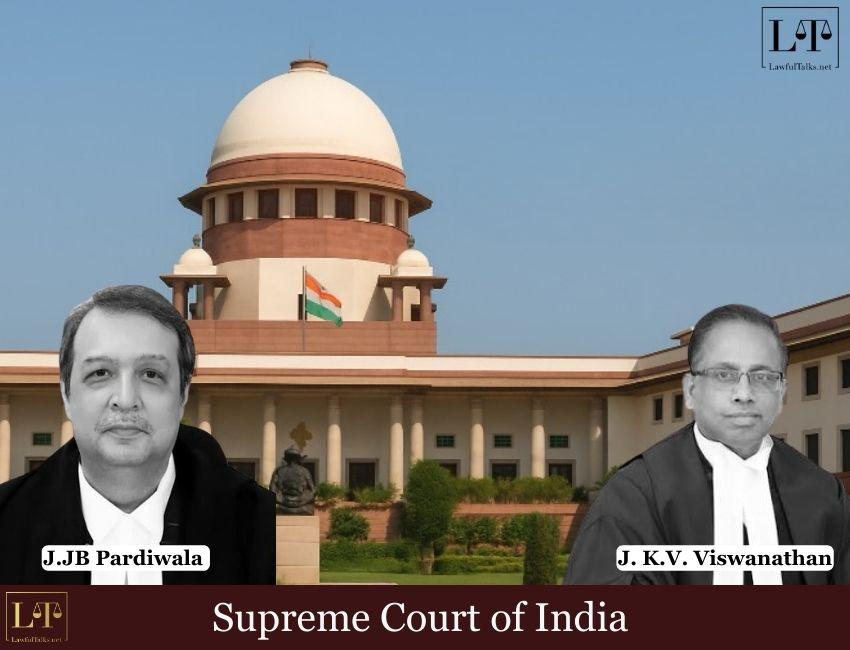

In a recent criminal appeal before the Division Bench of Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice Manoj Misra, the Supreme Court overturned the Allahabad High Court’s decision, which had dismissed the application by the Delhi Race Club (1940) to quash the summoning order issued by the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate. The Bench allowed the appeal and set aside the impugned order.

The Court held that while the Delhi Race Club, as a body corporate, could be held liable under the Indian Penal Code, the Secretary and President could not be held vicariously liable for offenses under Sections 406 and 420 of the IPC. The Court also elaborated on the legal distinctions between Criminal Breach of Trust and Cheating, clarifying that these offenses are mutually exclusive and cannot be simultaneously applied to the same set of facts.

The Original Complainant lodged a Private Complaint before the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate against the Delhi Race Club (1940) and its office-bearers, being Secretary and President, alleging offenses under Sections 406 (Criminal Breach of Trust), 420 (Cheating), and 120-B (Criminal Conspiracy) of the IPC. The complaint involved an unpaid amount of Rs.9,11,434/- for horse grains and oats supplied to the Club by the Complainant. It was contended that this amount was due from the Club and its office-bearers.

The Trial Court initiated a magisterial inquiry under Section 202 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC), and based on the recorded statements, issued a process for the offense under Section 406 (Criminal Breach of Trust) of the IPC. The Club and its office-bearers challenged this decision by filing an application under Section 482 of the CrPC before the High Court, seeking to quash the summoning order. The High Court, however, dismissed their application, observing that the Club’s failure to pay the due amount appeared to be intentional and that the complaint indicated a prima facie case of criminal breach of trust.

The Division Bench criticised the High Court’s decision, describing it as a fine specimen of total non-application of mind. The Court pointed out that the complaint included allegations under Sections 406, 420, and 120-B of the IPC, yet the Trial Court took cognizance and issued proceedings solely for the offense of criminal breach of trust as defined under section 405 of the IPC and made punishable under Section 406 of the IPC. The Bench emphasized that summoning an accused is a serious judicial action that requires thorough examination of the complaint, evidence, and the law to ensure that the issuance of process is justified.

The Court elucidated that the Indian Penal Code does not provide any provisions for attaching vicarious liability for office-bearers of a corporate entity. Consequently, the Secretary and President could only be held liable if there were direct allegations against them. The Court observed that the Magistrate failed to evaluate whether the complaint, even if accepted in its entirety, indicated personal liability for the Secretary and President.

Additionally, the Court highlighted that the High Court overlooked the procedural nuance that a Magistrate, when ordering a police investigation under Section 156(3) of the CrPC, does not take cognizance of the complaint. Cognizance is only taken upon receiving the police report. Hence, at the pre-cognizance stage, the Magistrate is required to scrutinize the complaint carefully to determine whether an offense is disclosed. This scrutiny becomes even more crucial when taking cognizance of a private complaint and issuing process.

The Court reiterated that “issuance of summons is a serious matter and, therefore, should not be done mechanically and it should be done only upon satisfaction on the ground for proceeding further in the matter against a person concerned based on the materials collected during the inquiry.”

The Court provided a detailed comparison of criminal breach of trust (section 406 of the IPC) and cheating (section 420 of the IPC), based on the Supreme Court’s decision in S.W. Palanitkar v. State of Bihar (2002) 1 SCC 241 and Harmanpreet Singh Ahluwalia v. State of Punjab, (2009) 7 SCC 712.

In order to constitute a criminal breach of trust under Section 406 of IPC:

1. There must be entrustment with person for property or dominion over the property, and;

2. The person entrusted: –

a) dishonestly misappropriated or converted property to his own use, or

b) dishonestly used or disposed of the property or willfully suffers any other person so to do in violation of:

i. any direction of law prescribing the method in which the trust is discharged; or

ii. legal contract touching the discharge of trust.

Essential ingredients of Cheating under Section 420 of IPC:

- deception of any person, either by making a false or misleading representation or by other action or by omission;

- fraudulently or dishonestly inducing any person to deliver any property, or

- the consent that any persons shall retain any property and finally intentionally inducing that person to do or omit to do anything which he would not do or omit.

The Court clarified that a mere breach of contract does not equate to criminal breach of trust or cheating unless there is evidence of fraudulent intent from the beginning of the transaction. In this case, the failure to pay for goods sold was a civil issue, not a criminal one.

The Court concluded that no case of criminal breach of trust or cheating was established. The complainant’s appropriate recourse would have been to file a civil suit for recovery of the amount due.

Case Details: Delhi Race Club (1940) Ltd. & Ors. v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr., Cri.Appeal/311/2024

(For more updates, tap to join our Whatsapp Channel and our LinkedIn Page)

Asmi Desai

Advocate, High Court

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 336 Posts

- High Courts 352 Posts