Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

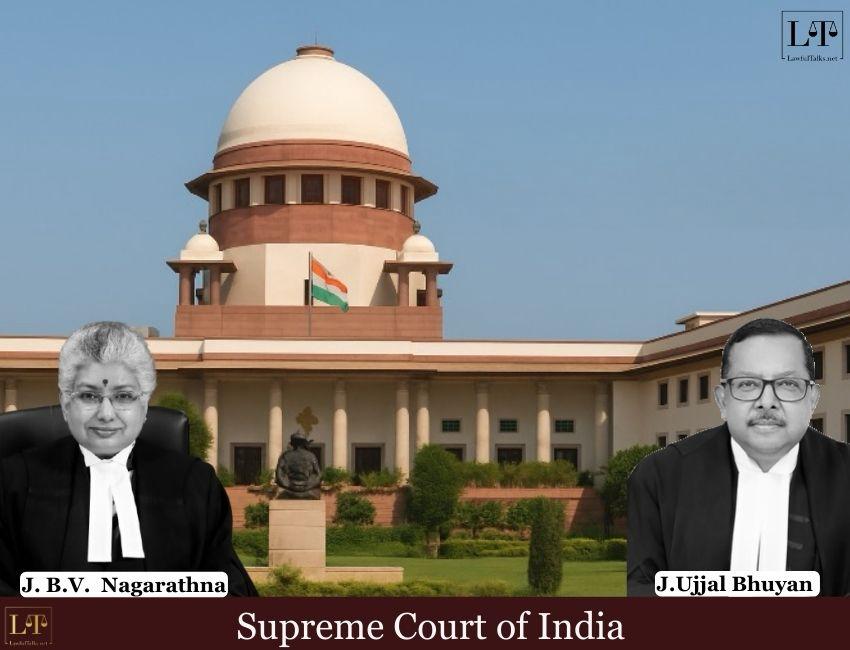

In a significant ruling reaffirming judicial authority in the investigative process, a bench comprising Chief Justice (CJI) B.R. Gavai and Justice K. Vinod Chandran of the Supreme Court have declared that a Magistrate possesses the power to order the collection of voice samples not only from accused individuals but also from witnesses.

Emphasizing that such samples—whether voice, fingerprints, handwriting, or DNA—constitute material evidence rather than testimonial evidence, the Court held that collecting them does not violate the protection against self-incrimination under Article 20(3).”

Building upon the 2019 precedent Ritesh Sinha v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr, the Bench reiterated that even though the Criminal Procedure Code(Cr.P.C.) does not expressly mention this power, a Judicial Magistrate can still direct any “person” to provide a voice sample for investigative purposes.

The Court underscored that the term “person” in Ritesh Sinha v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr was deliberately chosen to include not just the accused but also witnesses.

“It was held in Ritesh Sinha that despite absence of explicit provisions in Cr.P.C., a Judicial Magistrate must be given the power to order a person to give a sample of his voice for the purpose of investigation for a crime. We specifically note that this Court had not spoken only of the accused and specifically employed the words 'a person', consciously because the Rule against self-incrimination applies equally to any person whether he be an accused or a witness.”, stated the court .

Background:

The judgment stems from a 2021 case concerning the death of a young woman, which triggered mutual accusations between her family and in-laws. During the course of investigation, police alleged that a key witness (the 2nd respondent) had acted as an intermediary for the woman’s father and intimidated another witness.

To verify these claims, the Investigating Officer(IO) sought permission to record the witness’s voice sample for comparison with existing call recordings, and the Magistrate granted the request. However, the Calcutta High Court later intervened, setting aside this directive on the ground that the broader question of a Magistrate’s authority to order such sampling was then awaiting a decision before a larger Bench of the Supreme Court.

Overruling the High Court’s judgment, Justice Chandran, who authored the opinion, clarified that the pendency of a reference before a larger Bench does not cancel or pause the effect of an existing Supreme Court precedent.

The judge observed that the Ritesh Sinha v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr ruling continues to hold full force, empowering Magistrates to direct voice sampling as a form of material evidence until Parliament formally incorporates an explicit provision in procedural law.

The Bench further noted that the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) has now introduced Section 349, which expressly recognizes the authority of Magistrates to collect voice samples. Reiterating the principle that such sampling is a collection of physical evidence and does not compel a person to testify against themselves, the Court stated that Article 20(3) remains unaffected.

“If it is the BNSS that is applicable, then there is a specific provision enabling such sampling. The reasoning was also that mere furnishing of a sample of the fingerprint, signature or handwriting would not incriminate the person as such. It would have to be compared with the material discovered on investigation, which alone could incriminate the person giving the sample, which would not fall under a testimonial compulsion, thus not falling foul of the rule against self-incrimination.”, the court said, referring to Ritesh Sinha, which cited State of Bombay v. Kathi Kalu Oghad, AIR 1961 SC 1808.

Conclusively, the Supreme Court allowed the appeal and restored the Magistrate’s order authorizing the collection of the voice sample, reaffirming that such measures are lawful and follow due process.

Case Detail: Rahul Agarwal V. The State of West Bengal & Anr.

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts