Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

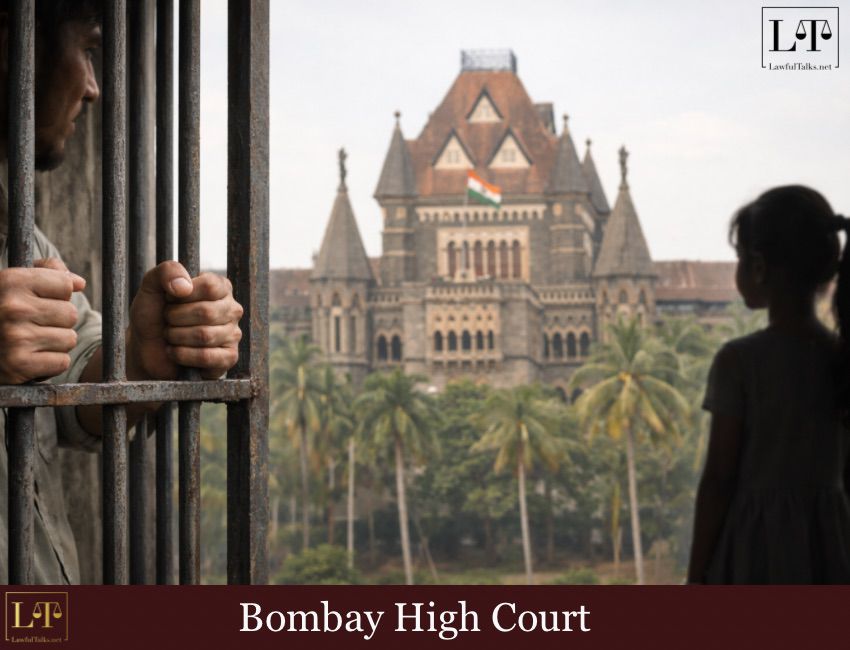

The Supreme Court of India, led by Justice Dipankar Datta and Justice Augustine George Masih, has ordered the immediate release of a man who has languished in prison for over four decades for a murder he committed as a 12-year-old boy in 1981, underscoring that the passage of time cannot nullify the legal protections granted to minors under the law.

Background:

The case originated in the Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh, where the petitioner, aged 12 years and 5 months at the time, was convicted of murder following a sessions court trial that found him guilty. However, the Sessions Court, having noted that the petitioner was aged about 16 years, held that he was entitled to the benefit of the Children's Act, 1960.

Accordingly, instead of sending the petitioner to jail, he was directed to be kept in a children’s home in accordance with the provisions of the 1960 Act, to give him a chance to reform himself. All the convicts, including the petitioner, challenged the conviction and sentence before the High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench, in an appeal under Section 374(2), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Vide a judgment and order dated 7th April, 2000, the High Court acquitted the appellants and allowed the appeal.

The State appealed this decision before the Supreme Court in 2009, which reversed the acquittal on May 8, restoring the sessions court's order of conviction and sentence, but with an absconding note regarding the petitioner, leading to his eventual arrest and lodging in Agra Central Jail on May 19, 2022.

Approaching the apex court via a petition filed under Article 32 of the Constitution seeking release from prison, the core question before the bench was whether the petitioner remained entitled to the benefits of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000, as amended by Act 33 of 2006, despite the elapsed years.

Advocate for Petitioner, argued that he had been behind bars for more than three years and eight months, deserving the maximum period of detention under Section 15(1)(g) of the JJ Act, 2000, and that extending it beyond three years in excess of such period would amount to illegal detention in clear breach of Article 21 of the Constitution of India, warranting his immediate release from illegal detention.

The State contended that since the date of occurrence of the crime was November 2, 1981, the 1960 Act would be applicable and not the JJ Act, 2000. The Bench recorded that under Section 7-A of the JJ Act, 2000, a plea of juvenility can be raised at any stage, even after the case has proceeded finally and even after final disposal in a trial at any stage before the Supreme Court.

On a plain reading of Section 7-A, courts are under an obligation to consider the plea of juvenility and to grant appropriate relief if it is found that the convict was a juvenile on the date of the offence. This statutory mandate requires courts to grant such relief once it is undisputed that the person was a child when the offence occurred.

The Supreme Court noted that the petitioner had already spent more than three years in custody, such confinement was unlawful and violated the constitutional right to personal liberty. “No provision in the 1960 Act has been brought to our notice that creates a legal impediment and thus, limits our authority to grant relief to the petitioner,” the Court said.

“Since there is no quarrel with the fact that the petitioner was a child at the time of commission of the offence and the petitioner having been

behind bars for more than 3 years, his liberty has been curtailed not in accordance with procedure established by law. Breach of the right guaranteed by Article 21 is writ large and, hence, the benefit of release from detention ought to be extended to the petitioner.” the court said

The Bench said that the continued incarceration was contrary to the procedure established by law and could not be sustained. The apex court also noted that the original trial had violated Section 24 of the 1960 Act, which barred joint trials of children with adults who were also accused.

“We have also not been shown by Mr. Shekar why provisions contained in Section 24 of the 1960 Act - prohibiting joint trial of a child with a person who is not a child - was observed in the breach.” the judgement stated.

The Court noted that this safeguard had not been followed when the petitioner was tried along with adults nearly four decades earlier. The Bench observed that the direction given by the trial court in 1984 to keep the petitioner in a children's home could not now serve its intended purpose because of the passage of time.

“The petitioner has suffered incarceration for more than the permissible law. Moreover, the purpose for which the Sessions Court directed the petitioner to be kept in a children's home is no longer feasible now,” the Court said.

Hence, the Court directed the petitioner's release from jail after concluding that his detention was illegal and that he had already served more than the period allowed under law.

“The Senior Superintendent, Central Jail, Varanasi, shall act on the basis of a downloaded copy of this judgment and order as and when produced, without insisting for a certified copy thereof.”

Case Details: Hansraj Vs. State of UP, WP(CRL) No. 340/2025

Appearance:

Advocate for Petitioner: Parinav Gupta, Pardeep Gupta, Mansi Gupta, Rakshit Rathi, Anuj Kumar Garg and Vipin Gupta.

Advocates for State : Neeraj Shekhar, Yashveer Singh, Shivansh Pundir and Rohit K Singh

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts