Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

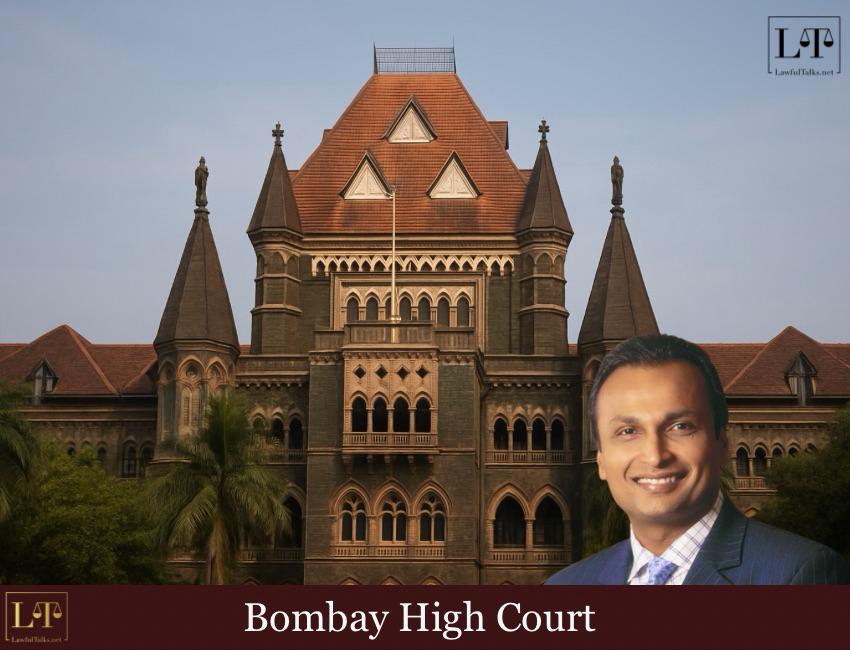

On the 14th of May 2025, as the nation watches with measured breath, Justice Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai took oath as the 52nd Chief Justice of India, a moment both momentous and meditative. His elevation is not merely ceremonial; it is a testament to decades of quiet jurisprudence, constitutional fidelity, and an unwavering commitment to the balance of powers that guards Indian democracy. The gavel he now inherits is no stranger to his hand, it is the same he has wielded to speak, not for himself, but for the Constitution.

Born on 24 November 1960 in Amravati, Justice Gavai’s legal journey began under the tutelage of Bar. Raja S. Bhonsale, a former Advocate General and High Court Judge. But his own legacy was never borrowed, it was carved independently through long years of advocacy at the Nagpur Bench and principled service on the bench of the Bombay High Court. Appointed as a judge of the Supreme Court in 2019, Justice Gavai soon became known not for judicial flamboyance, but for clarity, restraint, and a deep-rooted sense of constitutional purpose.

Over the years, he has been a part of nearly 700 Benches, but some decisions rise above the rest, not merely for their legal significance, but for the constitutional conscience they reflect. Among the most resonant judgments of Justice B.R. Gavai’s career is the landmark ruling in Association for Democratic Reforms v. Union of India (2024). Sitting on a Constitution Bench, Justice Gavai helped author the verdict that struck down the Electoral Bonds Scheme, a mechanism which had allowed for anonymous political donations through bearer instruments. The Court held that the scheme violated the citizen’s right to information under Article 19(1)(a) and dismantled the transparency essential to a functioning electoral democracy. It condemned the veil of secrecy that cloaked political financing, ruling that democracy cannot thrive in the dark, nor can electoral integrity survive the silence of concealed contributions.

Yet in Vivek Narayan Sharma v. Union of India (2023), Justice Gavai authored the majority opinion upholding the 2016 demonetisation initiative, an executive act that extinguished ₹500 and ₹1000 currency notes overnight. The judgment acknowledged the extraordinary sweep of the measure, but concluded that it was undertaken in accordance with Section 26(2) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, following due consultation with the RBI’s Central Board. The judgement held that policy-making, especially in the economic domain, lies primarily within the wisdom of the legislature and executive, and should not be second-guessed by the courts unless found unconstitutional or arbitrary.

He was also part of the five-judge Constitution Bench in In Re: Article 370 of the Constitution, which unanimously upheld the abrogation of Article 370. The Court held that Article 370 was a temporary provision, and its continuation beyond the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir did not grant it permanent status. Justice Gavai concurred with the reasoning that the President was empowered to issue the notification under Article 370(3), and that the reorganisation of the State into Union Territories under Article 3 was constitutionally valid. The judgment reaffirmed the plenary authority of Parliament to legislate uniformly for all parts of India, including Jammu and Kashmir

In State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh, Justice Gavai delivered a separate but concurring opinion that helped reshape the contours of affirmative action. He held that the earlier ruling in E.V. Chinnaiah, which had disallowed sub-classification within Scheduled Castes, could no longer be sustained. Supporting a more refined approach to distribution, he accepted that the “creamy layer” concept could extend to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, provided the criteria were contextually appropriate. He maintained that reservation benefits should not be perpetually conferred on socially advanced groups within disadvantaged communities.

In Re: Directions in the matter of demolition of structures, commonly referred to as The Bulldozer Demolition Case, Justice B.R. Gavai, along with Justice K.V. Viswanathan, held that demolitions must strictly follow due process and cannot be carried out as a form of punishment. The Court ruled that the state cannot act as judge, jury, and executioner. Affirming the constitutional value of shelter, Justice Gavai observed: “To have one’s own home, one’s own courtyard – this dream lives in every heart. It’s a longing that never fades, to never lose the dream of a home.”

In the realm of civil liberties, his rulings have been bold in defence of freedom. In Teesta Atul Setalvad v. State of Gujarat, bail was granted to the activist, calling the High Court’s refusal “perverse” and asserting that continued custody served no purpose when the evidence was largely documentary and custodial interrogation was complete. In Rahul Gandhi v. Purnesh Ishwarbhai Modi & Anr., the conviction was stayed in a criminal defamation case, criticizing the trial court for imposing the maximum sentence without adequate justification, and highlighting that such a conviction not only curtailed personal liberty but also undermined the democratic rights of the electorate.

Justice B.R. Gavai, as part of the Constitution Bench in Neeraj Dutta v. State(Govt. Of N.C.T. Of Delhi), upheld that circumstantial evidence can validly establish guilt under the Prevention of Corruption Act, even when the complainant turns hostile or is unavailable. This judgment resolved conflicting precedents and affirmed that the legal presumption under Section 20 of Prevention of Corruption Act 1988 may arise without direct evidence, provided demand and acceptance are inferentially proven.

He also authored decisive opinions in commercial arbitration, especially in the matter concerning the interplay between the Arbitration Act and the Stamp Act, where he clarified that unstamped arbitration agreements remain valid. In doing so, he cut through procedural thickets to uphold party autonomy and advance the ease of doing business.

Justice Gavai has never treated the courtroom as a theatre of ego. His judgments are not loud; they are lucid. His words, often laced with philosophical undertones, invoke both Aristotle and Iqbal, reminding young lawyers and old judges alike that “learning is an ornament in prosperity, a refuge in adversity, and a provision in old age.” Ending one of his speeches, he quoted Abraham Lincoln: “The best way to predict the future is to create it,” and then turned to the poetry of Allama Iqbal: “Khudi ko kar buland itna ki har taqdeer se pehle Khuda bande se khud poochhe, bataa teri razaa kya hai.”

As he ascends to the highest judicial office in the land, the robe he wears comes stitched with years of institutional wisdom and a deep, constitutional humility. His legacy, already inked in citations and footnotes, now turns a new page, one where the Chief Justice of India must not only decide for today but safeguard the soul of the Republic for tomorrow.

Asmi Desai, Law Intern

Sonam Pandey, Law Intern

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts