Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

In a notable ruling that reinforces procedural safeguards during criminal investigations, the Supreme Court has held that electronic service of notice under Section 35 of the BNSS, 2023 is not permitted. Any change would require legislative amendment, not judicial interpretation.

The decision reinforces that technology cannot override personal liberty. Although efficiency is important, basic legal safeguards must remain intact—especially when a person’s freedom is on the line.

The ruling was delivered in the aftermath of the dismissal of an application by the State of Haryana, seeking to allow electronic service of notices on WhatsApp or email—under Section 35 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023.

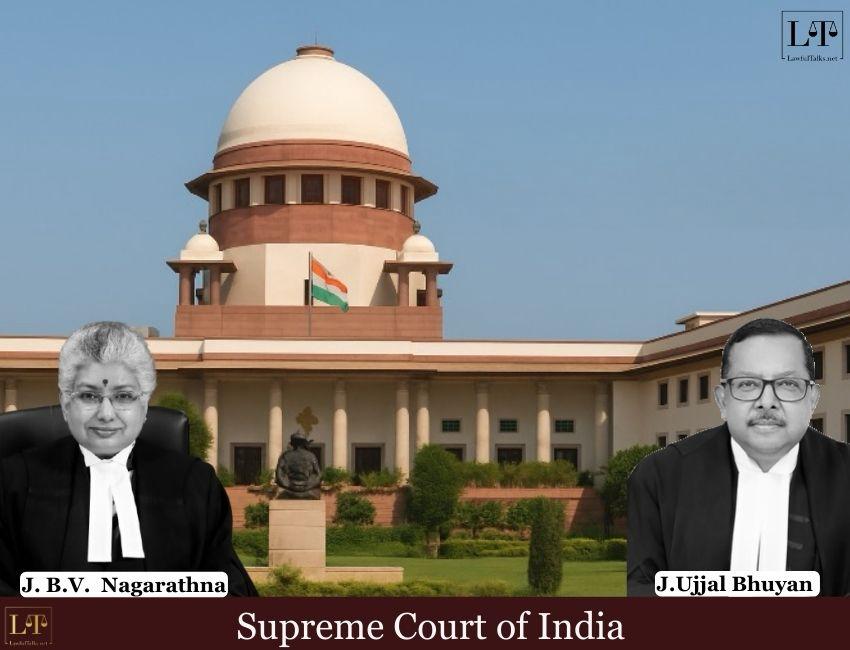

Justice MM Sundresh and Justice NK Singh presided over the bench .

The Background

The controversy arises under Section 35 of BNSS which empowers the police to issue a notice of appearance in lieu of arrest—making it a critical provision balancing state power and personal liberty. The Supreme Court has directed all States and Union Territories to strictly ensure that such notices are served only through physical modes prescribed under the law and not through WhatsApp or emails.

However, the State of Haryana filed an application to modify this order, arguing that:

-

Electronic service is efficient and helps prevent evasion.

-

BNSS provisions (Sections 64(2), 71, and 530) permit e-communication.

-

The legal system needs to adapt to technology.

Facts

In response to the IA No. 63691 of 2025 filed by the State of Haryana, the Supreme Court refused to dilute its earlier directive mandating that notices under Section 41-A of CrPC or Section 35 of BNSS be served strictly via officially prescribed methods—excluding WhatsApp or other electronic means.

The Court emphasized that electronic service lacks legal sanctity unless it aligns with procedures under Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC)/BNSS. Reiterating procedural fairness, it also reinforced that Standing Orders be strictly followed as per rulings in Rakesh Kumar v. Vijayanta Arya 2021 and Amandeep Singh Johar v. State 2018 (NCT Delhi)—precedents already upheld in the landmark Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI [(2022) 10 SCC 51].

Submissions on behalf of the Applicant (State of Haryana)

-

Nature of Notice under Section 35 BNSS is merely an intimation to join investigation, not an arrest warrant — thus, electronic service is practical and efficient.

-

Section 64(2) of BNSS allows electronic service of summons, indicating no bar on using digital means for similar notices like those under Section 35.

-

Section 71 BNSS: Permits electronic service of summons to witnesses without the need for a court seal — interpreted as an overriding provision supporting digital communication.

Distinction Between BNSS Sections 64 and 71:

-

Section 64 relates to system-generated e-summons, requiring authentication (like court seal).

-

Section 71 covers scanned physical summons sent electronically — no seal required, analogous to Section 35 notices.

-

Section 530 of BNSS demonstrates legislative intent to digitally streamline criminal proceedings; thus, excluding Section 35 notices from electronic service contradicts this goal.

Inapplicability of Prior Case Law:

-

Delhi HC rulings (Rakesh Kumar and Amandeep Singh Johar), upheld in Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI (2022), were based on the CrPC, 1973, which lacked digital provisions.

-

BNSS, 2023 includes statutory recognition of electronic communication, making prior guidelines irrelevant.

Submissions on behalf of the Amicus Curiae

-

Electronic service not recognized under Section 35 BNSS where Notices served via WhatsApp or other digital modes are not contemplated as valid under Section 35, since they do not align with Chapter VI of BNSS, 2023.

-

Summons require personal service as per standard legal practice, personal service is mandatory, and only under specific conditions (i.e., presence of court seal) is electronic service permitted under Section 64(2) proviso.

-

Section 35 notices are not court-issued since such notices are issued by Investigating Agencies and not by courts, they cannot be served electronically, as they do not fulfill the requirement of bearing a court seal.

-

Section 530 excludes investigation: This section allows electronic mode for trials, inquiries, and proceedings, but explicitly omits investigations, indicating that the investigation phase is excluded from digital procedures.

-

As non-compliance with a Section 35 notice can lead to arrest, it is imperative for such notices to be served personally, ensuring due process and safeguarding the accused's liberty.

-

These submissions argue for strict adherence to physical service for Section 35 notices, emphasizing legal safeguards, procedural integrity, and legislative intent.

The Supreme Court’s Take: Liberty Comes First

The Supreme Court has construed Section 35 of the BNSS as a liberty-protective measure. Allowing electronic service without personal delivery mechanisms opens the door to serious abuse. If a citizen never receives the notice but is arrested for non-compliance, it would be a gross violation of Article 21 of the Constitution, observed the court.

The Supreme Court further clarified that Section 530 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) permits the use of electronic communication only in the context of trials, inquiries, or other judicial proceedings, and not during the course of police investigations.

The Court also distinguished that, unlike summons which are issued by courts, a notice under Section 35 of the BNSS is issued by the police in the exercise of their investigative powers, and does not emanate from judicial authority.

The court particularly emphasised on interpretation of law which does not mention e-services in Section 35 of BNSS. There are also other sections in BNSS like Sections 94 and 193 that specifically allow for electronic communication—but not for arrest-related notices.

Final Holding:

After due examination the Supreme Court concluded that electronic service of notice under Section 35 of the BNSS, 2023 is not permitted. Any change would require legislative amendment, not judicial interpretation.

Case Details : SATENDER KUMAR ANTIL. V. CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION AND ANR. (Special Leave Petition) crl. 5191/2021

Aishwarya Yashwantrao

Advocate, Bombay High Court

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts