Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

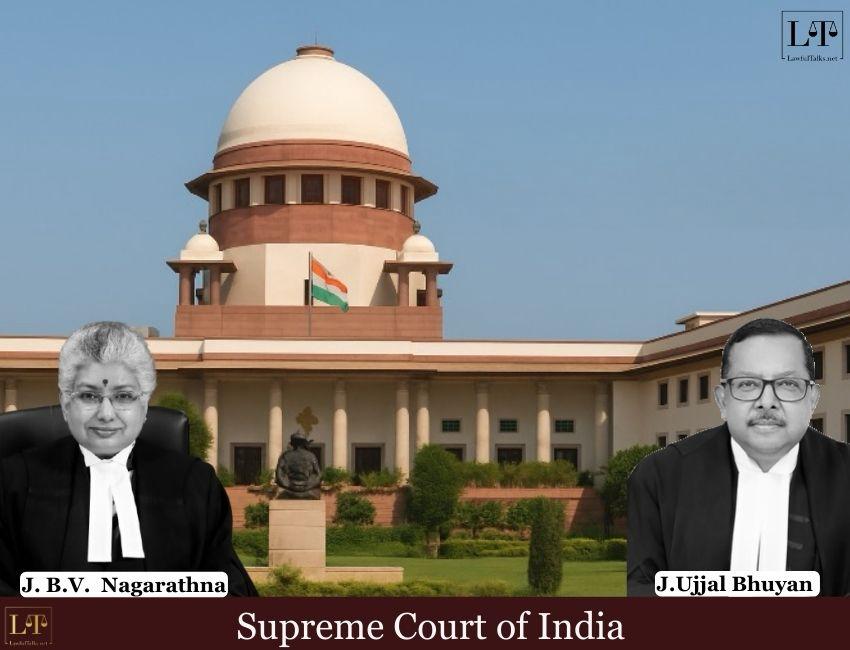

SC Justices Nagarathna and Dhulia Disagree on CJI’s “Harsh” Comments, Defend Krishna Iyer’s Legacy in Article 39(b) Interpretation

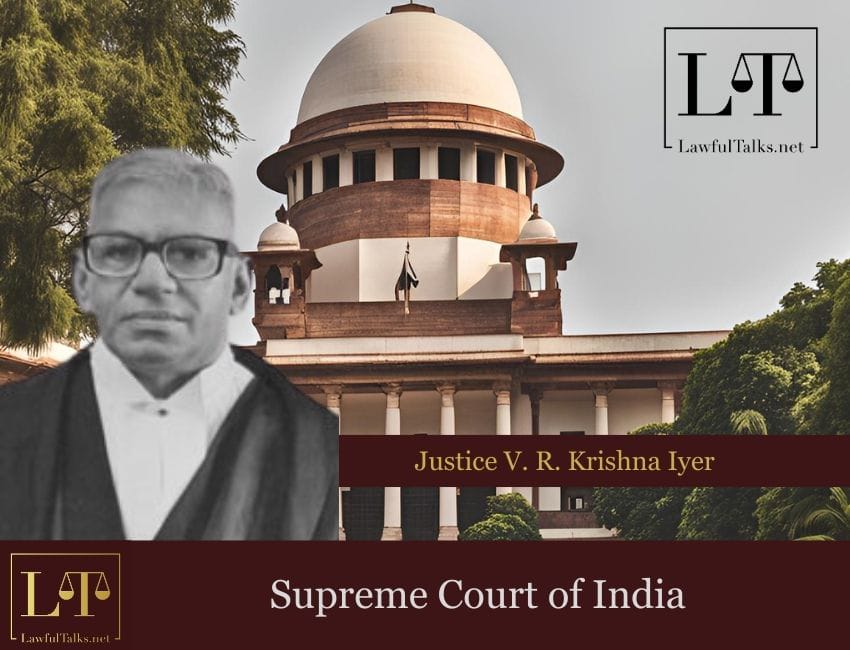

In the recent Supreme Court judgement on the interpretation of Article 39(b), a sharp divide emerged as Justices B.V. Nagarathna and Sudhanshu Dhulia disagreed with Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s remarks regarding the judicial legacy of Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer. Justice Nagarathna characterised CJI Chandrachud’s critique of Justice Krishna Iyer’s broader interpretation as “unwarranted and unjustified,” while Justice Dhulia described it as “harsh” and avoidable.

The legal journey leading up to this judgement began with the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Act, 1976 (MHADA Act), which aimed to address housing challenges in Mumbai. The Act imposed a cess for repair and reconstruction of dilapidated buildings, transferring control of certain properties to cooperative societies in the public interest. These provisions, however, faced constitutional challenges under Articles 14 and 19. The Maharashtra government argued that the Act was protected under Article 31C, which grants immunity from such challenges if a law gives effect to the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs) under Article 39(b).

The High Court upheld this stance, leading to appeals in the Supreme Court. Three reference orders followed, each adding complexity and expanding the need to review the broad interpretation of Article 39(b), previously supported by Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer in State of Karnataka v. Ranganatha Reddy (1978) and subsequently in Sanjeev Coke Manufacturing Co. v. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd. (1983). Ultimately, the case was referred to a nine-judge bench, emphasizing the need to revisit the legacy of expansive interpretations surrounding Article 39(b).

These interpretations, however, were not without contention, regarding whether privately-owned resources could fall within the ambit of “material resources of the community.” The nine-judge bench was thus tasked with determining whether such an expansive interpretation aligned with the framers' original intent.

Assenting Observations

Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud authored the majority opinion, observing that an expansive reading of Article 39(b) would risk undermining the constitutional protections afforded to private property. He argued that “material resources of the community” should be limited to inherently public or community-held resources and not extended to privately-owned assets. The majority expressed concern that endorsing a broad interpretation could disrupt the delicate constitutional balance, a balance that the framers carefully sought to maintain.

CJI Chandrachud observed, “the role of this Court is not to lay down economic policy, but to facilitate this intent of the framers to lay down the foundation for an ‘economic democracy’.” He criticised what he termed the “Krishna Iyer doctrine” from Ranganatha Reddy, which he viewed as promoting an economic ideology that risked constraining private ownership under the guise of public interest. He stated “The doctrinal error in the Krishna Iyer approach was, postulating a rigid economic theory, which advocates for greater state control over private resources, as the exclusive basis for constitutional governance.

CJI Chandrachud also referenced Sanjeev Coke Manufacturing Co., where Justice Chinnappa Reddy endorsed Krishna Iyer’s view. However, CJI Chandrachud’s majority opinion rejected this precedent.

Supporting CJI Chandrachud, Justices J.B. Pardiwala, Rajesh Bindal, Manoj Misra, Satish Chandra Sharma, Hrishikesh Roy, and Augustine George Masih accentuated the majority’s cautious interpretation. They observed that while, in theory, the phrase may include privately owned resources, it declined to endorse the expansive interpretation previously proposed by Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer. This interpretation, which originated in State of Karnataka v. Ranganatha Reddy and was later relied upon in Sanjeev Coke Manufacturing Co. v. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd. The Court emphasised that not all privately held assets could qualify as “material resources of the community” merely by addressing “material needs,” as the interpretation should be context-specific and involve careful evaluation. The Court reaffirmed the validity of Article 31C to the extent upheld in Kesavananda Bharati v. Union of India, ensuring certain laws aimed at fulfilling Directive Principles, including Article 39(b), are protected from challenges under Articles 14 and 19.

Dissenting Observations

Justice B.V. Nagarathna expressed strong disapproval of Chief Justice Chandrachud’s remarks regarding Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer’s interpretive approach to Article 39(b). She characterised these criticisms as “unwarranted and unjustified” and argued that Justice Krishna Iyer’s perspective should be viewed within the socio-economic context of the 1970s, an era in which redistributive justice was seen as central to achieving the Constitution’s vision of equality. Justice Nagarathna argued that the expansive interpretation of Article 39(b) offered by Justice Krishna Iyer was in line with the framers’ intent to promote economic democracy and equitable distribution.

Justice Nagarathna suggested that such remarks could affect the judiciary’s legacy, stressing the importance of understanding past decisions within their socio-economic and constitutional context. She observed:

"Regardless, on a conspectus understanding of all contributing factors such as the discussions in the Constituent Assembly and the tide of the times that found in the broad house of economic democracy a legitimate State policy, can we castigate former judges and allege them with ‘disservice’ only for reaching a particular interpretive outcome?"

Justice Nagarathna’s dissent pointedly emphasised that judicial interpretations should not be undermined due to changes in economic policy. Reflecting on the sweeping liberalisation policies that emerged post-1991, she argued that these developments should not retroactively devalue the wisdom embedded in past doctrines. She contended:

“Merely because of the paradigm shift in the economic policies of the State to globalisation and liberalisation and privatisation, compendiously called the ‘Reforms of 1991,’ which continue to do so till date, cannot result in branding the judges of this Court of the yesteryears ‘as doing a disservice to the Constitution’.”

Justice Nagarathna maintained that judicial interpretations should adapt to current circumstances without erasing the contributions and insights of former judges who worked within different socio-economic frameworks.

Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia, supporting Justice Nagarathna’s dissent, emphasised the importance of Justice Krishna Iyer’s legacy, describing his philosophy as deeply embedded in “humanist principles of fairness and equity.” According to Justice Dhulia, Justice Krishna Iyer’s interpretations, often referred to as the “Krishna Iyer Doctrine,” emerged from a commitment to social justice and empathy for the people, guiding the judiciary through challenging times and promoting equitable development. He stated:

“The Krishna Iyer Doctrine…is based on strong humanist principles of fairness and equity. It is a doctrine which has illuminated our path in dark times.”

Justice Dhulia argued that the Krishna Iyer Doctrine was not an ideologically narrow or rigid economic theory, as suggested by Chief Justice Chandrachud, but rather a broader judicial philosophy that prioritised the human impact of economic decisions. He explained that Justice Krishna Iyer’s and Justice Chinnappa Reddy’s rulings demonstrated a profound commitment to the well-being of the populace, influenced by the framers’ vision of a just society. Justice Dhulia added:

“The long body of their judgment is not just a reflection of their perspicacious intellect but more importantly of their empathy for the people, as human being was at the centre of their judicial philosophy.”

Case Details- Property Owners Association & Ors. V. State of Maharashtra