Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

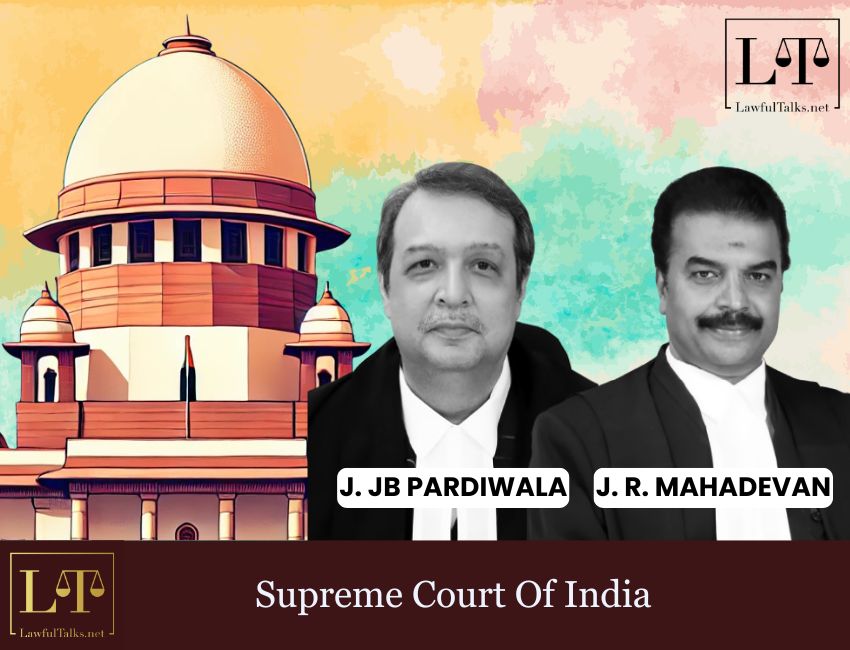

A Supreme Court bench of Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice R. Mahadevan recently overturned the murder conviction of a man, holding that the Chhattisgarh High Court wrongly relied on a confessional First Information Report (FIR) filed by the accused himself. The Court reaffirmed that a statement made by one accused in an FIR is inadmissible against another accused and, even for the maker, an inculpatory statement to a police officer cannot be used as evidence unless the accused appears as a witness.

“An FIR of a confessional nature made by an accused person is inadmissible in evidence against him, except to the extent that it shows he made a statement soon after the offence, thereby identifying him as the maker of the report, which is admissible as evidence of his conduct under Section 8 of the Act of 1872. Additionally, any information furnished by him that leads to the discovery of a fact is admissible under Section 27 of the Act of 1872. However, a non-confessional FIR is admissible against the accused as an admission under Section 21 of the Act of 1872 and is relevant,” the bench stated.

The Court further clarified: “Even as against the accused who made it, the statement cannot be used if it is inculpatory in nature nor can it be used for the purpose of corroboration or contradiction unless its maker offers himself as a witness in the trial. The very limited use of it is, as an admission under Section 21 of the Act of 1872, against its maker alone, and only if the admission does not amount to a confession.”

Facts:

The case concerned an incident on 27 September 2019, when the appellant approached Korba Kotwali Police Station and lodged a FIR for an offence under Section 302 IPC. Police later discovered the deceased’s locked residence, where his body lay in a pool of blood. A knife, other articles, and bloodstained clothes recovered from the appellant’s uncle’s house were seized. Post-mortem indicated death due to shock and lung injury caused by bleeding.

The Sessions Court convicted the appellant under Section 302 IPC and imposed life imprisonment. On appeal, the High Court altered the conviction to Section 304 Part I IPC, applying Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC.

The Supreme Court bench found “errors apparent on the face of the record” in the High Court’s approach, noting it had directly corroborated medical evidence with the accused’s own confessional FIR. “As observed earlier, the FIR lodged by the appellant amounts to a confession, and any confession made by an accused before the police is hit by Section 25 of the Act of 1872. There was no question at all for the High Court to seek corroboration of the medical evidence on record with the confessional part of the FIR lodged by the appellant,” the bench stated.

The Apex Court also criticised the High Court’s treatment of medical evidence, observing that while such an opinion can clarify the cause of death and nature of injuries, it cannot independently prove the guilt of an accused. Medical experts are not eyewitnesses, and their testimony is intended to assist the court with technical assessments, not to substitute for factual or circumstantial proof.

“The High Court should have been mindful of the fact that a doctor is not a witness of fact. A doctor is examined by the prosecution as a medical expert for the purpose of proving the contents of the post-mortem report and the medical certificates on record, if any. An expert witness is examined by the prosecution because of his specialized knowledge on certain subjects, which the judge may not be fully equipped to assess. The evidence of such an expert is of an advisory character,” the bench stated.

On the limits of relying solely on such evidence, the Court added that the prosecution’s other evidence was also weak.

“An accused cannot be held guilty of the offence of murder solely on the basis of medical evidence on record. So far as the panch witnesses are concerned, their depositions do not inspire any confidence. Most of the panch witnesses turned hostile. If at all, the public prosecutor wanted to prove the contents of the panchnamas after the panch witnesses turned hostile, he could have done so through the evidence of the investigating officer. However, the investigating officer also failed to prove the contents of the panchnamas in accordance with law. Thus, there is nothing on record by way of evidence relating to any discovery of fact is concerned. In other words, no discovery of fact at the instance of the appellant, relevant and admissible under Section 27 of the Act of 1872, has been established,” the Court observed.

As a note of caution, the Court stressed that while an accused’s conduct may be taken into account as a relevant fact under Section 8 of the Evidence Act, it can never be the sole foundation for conviction. Such behaviour is only one circumstance among many and must be assessed alongside credible direct or circumstantial evidence. Convicting solely on conduct, the Court warned, would be legally unsustainable, particularly in serious offences like murder.

“We deem it necessary to sound a note of caution. While the conduct of an accused may be a relevant fact under Section 8 of the Act of 1872, it cannot, by itself, serve as the sole basis for conviction, especially in a grave charge such as murder. Like any other piece of evidence, the conduct of the accused is merely one of the circumstances the court may consider, in conjunction with other direct or circumstantial evidence on record. To put it succinctly, although relevant, the accused’s conduct alone cannot justify a conviction in the absence of cogent and credible supporting evidence,” the bench remarked.

With the FIR excluded, the Court found no substantive evidence connecting the appellant to the killing. Several panch witnesses had turned hostile, panchnamas were not proved, and medical evidence alone was deemed insufficient for conviction. The High Court’s application of Exception 4 (sudden fight) was also found misplaced. If any exception applied, it would have been Exception 1 (grave and sudden provocation), but in the absence of legal evidence against the appellant, this remained academic.

Allowing the appeal, the Court acquitted the appellant of all charges and ordered his immediate release. It also directed circulation of the judgment to all High Courts to reinforce the principle that convictions must be based only on legally admissible evidence.

Case Details: Narayan Yadav Vs. State Of Chhattisgarh, Criminal Appeal No. 3343 of 2025.

Advocate for the Petitioner: Manjeet Chawla

Advocate for the Respondent: Prabodh Kumar

Anushka Bandekar

Advocate

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 347 Posts

- High Courts 361 Posts