Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

In a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court bench of Justice K. Vinod Chandran has clarified the limits of summoning lawyers during criminal investigations, marking an important step in defining advocate–client privilege and protecting the independence of the legal profession.

The judgment begins with a striking quote from Shakespeare’s Henry VI: “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” The Court explains that, though often seen negatively, the line actually shows Shakespeare’s understanding that removing lawyers would pave the way for a totalitarian regime. This sets the tone for the verdict, highlighting the vital role of lawyers in defending individual freedoms and constitutional rights.

Background:

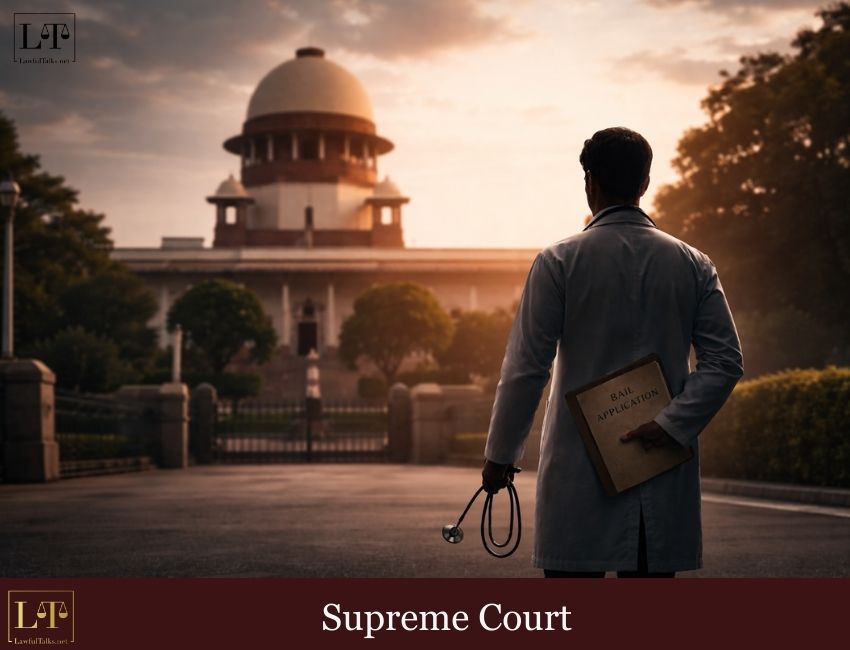

The case arose after an investigating agency issued a summons to an advocate, seeking his appearance to explain the details of a case in which he was representing the accused. The petitioners and several bar associations argued that this action undermined the legal and constitutional safeguards that protect private communication between a lawyer and their client.

The judgment recounts their arguments, stating, “The subject notice issued is an unconscionable, outrageous interference with the right to practice, conferred on the Advocates under Article 19(1)(g) and Article 21 of the Constitution of India,” and highlighting that “any interference with the obligation of non-disclosure of facts and circumstances pertaining to an alleged crime, by an Advocate representing the accused, is against the statutory protection conferred on the client.”

The Bar Council and senior lawyers cautioned that compelling such disclosures from lawyers and forcing them to reveal information would harm fair legal representation and could also lead to them being accused of ‘professional misconduct’.

The state, represented by the Attorney General and Solicitor General, acknowledged the sanctity of advocate-client privilege but urged that, “no Advocate can be summoned for reason only of giving a legal opinion or appearing for a party in a case. But the immunity with respect to professional communications would not absolve the liability in the event of an Advocate participating in a crime which is beyond his professional duty.”

The state’s position was that laws already offer sufficient safeguards, and that summoning should only occur in exceptional circumstances, as defined in the law itself.

Examining Indian and international precedents, the Supreme Court said that advocate-client confidentiality is not just a legal rule but an essential part of the right to have proper legal representation.

Quoting and interpreting Section 132 of the Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA), the Court observed: “An Advocate cannot be coerced into revealing any information with respect to the client he represents or the cause he is engaged to prosecute or defend.”

The judgment underscores that only three narrowly defined exceptions exist: where the client consents; where the communication furthers an illegal purpose; or where the lawyer, during his engagement, observes an ongoing fraud or crime. Outside these clear exceptions, the privilege is inviolable, protecting not just the accused but the entire justice delivery system.

Importantly, the Court clarified the boundaries of investigative powers under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS). “The power to summon... is not an absolute or a blanket power to be exercised, without looking at the provisions of Section 132 of the BSA. We cannot deny the power altogether or place fetters on it... but neither can we permit wholesale transgression… Any such summons issued as against a lawyer by an Investigating Officer has to be with the approval and satisfaction of the hierarchical Superior, not below the rank of a Superintendent of Police which satisfaction has to be recorded in writing and should mention the facts leading to the exception under Section 132, for which the summons is issued.” Equally important, “the lawyer summoned can challenge under Section 528 of the BNSS,” ensuring that the process is subject to judicial review.

The Court declined to create new guidelines or committees for the issuance of such summons, reasoning, “We are not satisfied that this Court could frame a guideline insofar as the procedure to be adopted in summoning a lawyer, which would be in addition to and for all practical purposes may, in effect, be in derogation of the provisions of the BNSS. The power of the police officer to investigate a cognizable offence... cannot be regulated by any guideline issued by us, especially when sufficient guideline is available, under Sections 132 to 134 of the BSA.” Instead, the Court said that the current laws are clear and sufficient, and that any misuse or overreach can be addressed through proper legal remedies.

The judgment also clarifies the position of in-house counsels, noting that, “the benefit of legal professional privilege... is subject to two cumulative conditions. First, the exchange with the lawyers must be connected to the clients’ rights of defence and, second, the exchange must emanate from independent lawyers, that is to say, lawyers who are not bound to the client by a relationship of employment. It follows that... legal professional privilege does not cover exchanges within a company or group with In-house lawyers.”

In sum, the Supreme Court set aside the police summons, holding it illegal and a breach of Section 132. It expressed concern that, “The facts and circumstances of a crime committed, or an FIR registered, is not to be elicited from the Advocate who represents the accused, which again is a reflection of the abject failure of the investigating agency,” and reaffirmed that, “The position of trust the Advocate occupies vis-à-vis his client cannot be put to test by an attempt to breach the professional confidence, conferred with a solemn privilege under Section 132 which has reflections of the constitutional protection against self-incrimination.”

The Court further stated, “We find the reasons stated of the Advocate having not responded to the summons and the investigation being stalled, to dismiss the petition, to be flawed and erroneous. It is also an abdication of the inherent powers conferred on the High Court, which the blatant breach of the rule against non-disclosure projects.”

The Supreme Court has now made it clear that while no lawyer is above the law, the core values of confidentiality and fearless legal representation are essential to a democracy.

Case Details :Special Leave Petition (Criminal) No. 9334 of 2025

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts