Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

In a strong rebuke, the Bombay High Court pulled up the Maharashtra police and state authorities for failing to comply with the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), which came into force in July 2024.

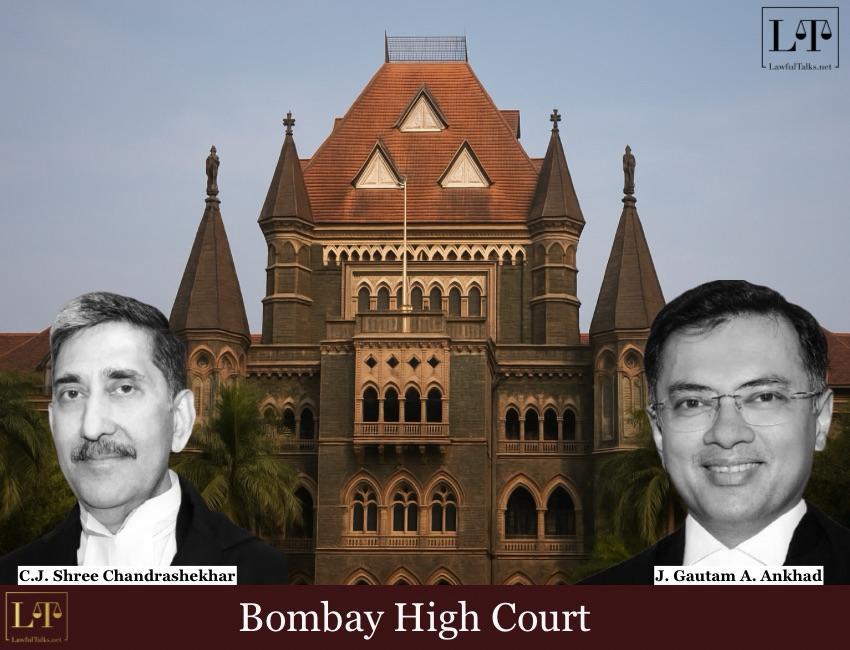

The court questioned why key procedures under the new criminal law were being ignored months after its implementation. A bench of Justice A.S. Gadkari and Justice Ranjitsinha Raja Bhonsale examined the issue and scrutinized this lapse while hearing three separate petitions and expressed concern over the continued sidelining of mandatory BNSS protocols.

The Bench also called upon the Union Home Ministry to clarify whether the BNSS has been formally communicated and made operational in police stations across Maharashtra.

If the law applies, the court directed senior police officials in the state to explain why its provisions were not being enforced with due diligence. It also permitted the Union of India to be added as a respondent and sought clear clarification on the scope of the law. “Whether BNSS is applicable to all police stations within the territorial jurisdiction of the Bombay High Court and, if so, why it has not been followed strictly and sincerely,” the Court said.

Background:

In the case filed by petitioner Mehul Jain, the judges drew attention to a summons issued by an Assistant Police Inspector from VP Road police station. The court noted that the summons was based on an entry in a so-called “Movement Register” and not on any authority recognised under the BNSS.

The Bench directed the Joint Commissioner of Police (Law and Order), Mumbai, to file an affidavit explaining whether the BNSS applies to the Mumbai police force and, if so, why officers were “issuing summons to citizens under some unknown procedure not even defined in the Maharashtra police manual.”

Expressing concern over the practice, the Court said, “We are regularly coming across with such sort of instances where the citizens of India are being summoned at police station by giving reference of ‘movement register’, which according to us prima facie is not proper.”

The court also criticised the police practice of prolonging “preliminary enquiries” without following the timelines set out in Section 173(3)(i) of the BNSS. The provision allows such enquiries—meant only to check whether a prima facie case exists—to last no more than fourteen days from the receipt of information.

However, in the petition filed by Kundan Jaywant Patil, the court found that the enquiry had continued for several months, well beyond the prescribed limit. Recording its concern, the Court said, “We regularly come across with cases wherein the police personnel and/or Police Stations within the territorial jurisdiction of this court are conducting preliminary enquiries leisurely as per their own whims and caprices and in utter disregard to the mandate of law, Section 173(3)(i) of BNSS”.

From these repeated violations, the Bench observed that police officers either appeared to be unaware of the BNSS or were deliberately ignoring its provisions.

Similarly, in the petition filed by Ashwin Ashirvad Parmar, which relates to a complaint monitored by the Maharashtra State Commission for Scheduled Caste and Tribe, the court directed the concerned Deputy Commissioner of Police to explain the delay in completing the mandatory enquiry or investigation within the fourteen-day limit prescribed under Section 173(3)(i) of the BNSS.

Case Details:

Mehul Jain V. State of Maharashtra & Ors (WRIT PETITION NO. 6462/2025)

Ashwin Ashirvad Parmar V. The State of Maharashtra & Anr. (WRIT PETITION NO. 6020/2025)

Kundan Jaywant Patil V. The State of Maharashtra & Ors. (WRIT PETITION NO. 5654/2025

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 352 Posts

- High Courts 367 Posts