Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

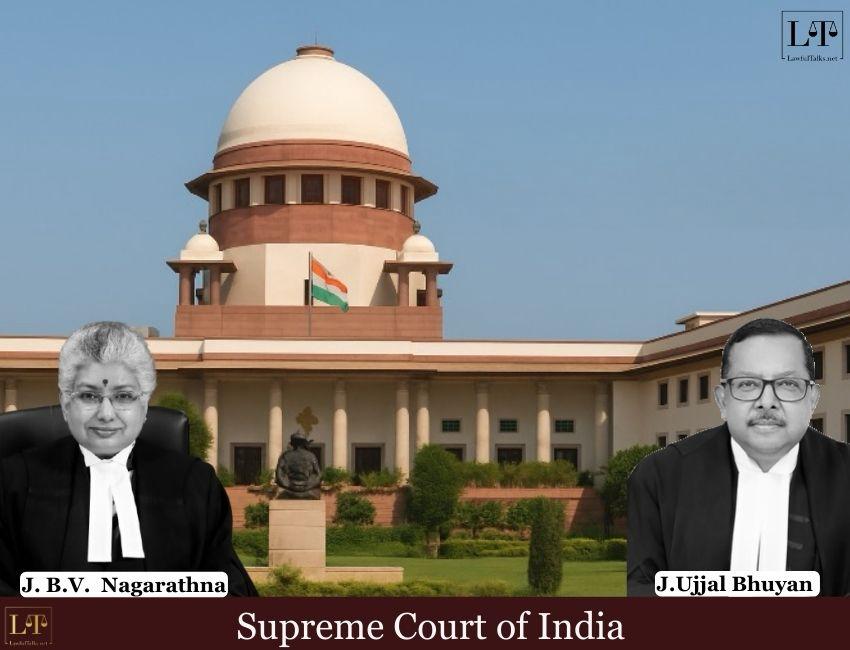

In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court of India, comprising Justices Sanjay Karol and N. Kotiswar Singh, allowed the State of Uttar Pradesh’s appeal against a controversial bail order passed by the Allahabad High Court. The Court set aside the High Court’s broad directions on how a victim’s age should be determined in POCSO cases, but it did not interfere with the bail granted to the accused, which was left intact.

This judgment comes at a time when courts have increasingly expressed concern over the misuse of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, especially in cases of consensual teenage relationships where ages are allegedly manipulated to misuse the law. In a strong post-script, the Supreme Court bench directly spoke about this broader problem. They said:

“Considering the fact that repeated judicial notice has been taken of the misuse of these laws, let a copy of this judgment be circulated to the Secretary, Law, Government of India, to consider initiation of steps as may be possible to curb this menace inter alia, the introduction of a Romeo – Juliet clause exempting genuine adolescent relationships from the stronghold of this law; enacting a mechanism enabling the prosecution of those persons who, by the use of these laws seeks to settle scores etc.”

The suggestion of a "Romeo-Juliet clause" specifically aims to remove criminal liability for consensual relationships between people close in age and suggests punishment for those who deliberately file false complaints.

Background:

The case originated from FIR No. 622 of 2022 registered at PS Kotwali, Orai, District Jalaun, where the mother of the alleged victim accused Respondent No. 1 Anurudh of abducting her 12-year-old daughter, invoking Sections 363 and 366 of the Indian Penal Code along with Sections 7 and 8 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012.

The trial court refused bail on September 29, 2023. After this, the accused approached the Allahabad High Court under Section 439 of the CrPC. During the proceedings, differences were found in the victim’s age as recorded in school documents, in statements given under Sections 161 and 164 of the CrPC, and in her statements about her relationship with the accused.

On April 22, 2024, the High Court directed the Chief Medical Officer of Jalaun to set up a medical board to determine the victim’s age. Interim bail was granted on May 8, 2024. In its final order dated May 29, 2024, the High Court confirmed the bail after the medical report stated that the victim was above 18 years of age. At the same time, the High Court issued wide directions requiring the police, in every POCSO case, to obtain a medical age determination report at the very beginning of the investigation under Section 164A of the CrPC read with Section 27 of the POCSO Act.

The Supreme Court focused on a key issue: whether the High Court, while deciding a bail plea under Section 439 of the CrPC, could order age-determination tests in all POCSO cases and issue broad, system-wide directions.

Supreme Court’s Analysis And Judgment:

Allowing the appeal, Justice Sanjay Karol, who wrote the judgment, explained that courts dealing with bail only examine whether a prima facie case exists. They must not conduct mini-trials or closely examine evidence. The court noted that this view has been confirmed many times in earlier judgments, including State of U.P. v. Amarmani Tripathi and Vaman Narain Ghiya v. State of Rajasthan.

"The jurisdiction of the court under Section 439 of the Code is limited to grant or not to grant bail pending trial," the bench emphasized, holding that a court’s power under Section 439 CrPC is limited to deciding whether bail should be granted or refused during the trial. It held that the Allahabad High Court was wrong to combine its limited bail powers with broader constitutional powers.

While examining the reasoning of the Allahabad High Court, the Supreme Court referred to earlier Allahabad decisions such as Monish v. State of U.P. and Aman Vansh v. State of U.P.. These cases had raised concerns about misuse of the POCSO Act in consensual teenage relationships, where ages were allegedly changed in records. They supported the idea that medical age reports should be relied on instead of documents that could be manipulated.

The order under challenge reproduced five directions. One of them stated: “The police authorities/investigation officers shall ensure compliance of the directions rendered by this Court in Aman supra and ensure that the medical report determining the age of the victim is drawn up by the competent medical authority at the commencement of the investigations of POCSO Act offences in accordance with the provisions of the Section 164-A CrPC read with Section 27 of the POCSO Act.”

Another direction required that such medical reports be placed before the court at the time of bail hearings, with courts checking whether these directions had been followed. It also said that, in appropriate cases, medical age findings should be given priority over school records.

However, the Supreme Court held that these directions went beyond the High Court’s bail powers. It compared this to earlier instances, such as State v. M. Murugesan, where courts had issued policy-like directions while dealing only with bail matters.

While interpreting the law, the Supreme Court clearly explained the relevant legal provisions. It noted that Section 27 of the POCSO Act requires a medical examination under Section 164A of the CrPC for offences under the Act. However, this provision is meant for victims of rape or attempted rape, and although age is one of the details to be noted, it does not require routine ossification or age-determination tests in every case.

The Court then referred to Section 94 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015. This section lays down a clear order for deciding age: first, a matriculation certificate; if that is not available, school records or a birth certificate; and only if these are not available can medical tests be used. The age recorded under this process is treated as final for the purposes of the JJ Act.

Relying on Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana, the bench said that the same approach applies to victims under the POCSO Act. Any dispute about the victim’s age must be decided during the trial, not at the bail stage, by examining evidence, including witnesses who can speak about the documents relied upon.

The judges clearly stated: “The determination of the age of the victim is a matter for trial, and the presumption which is accorded to the documents enumerated under the Section, has to be rebutted there.” They warned that deciding such issues at the bail stage would amount to holding a mini-trial and would improperly take over the role of the trial court.

The Court explained that the law treats the age of an accused and the age of a victim differently. Under the Juvenile Justice Act, the age of an accused person is decided by the Juvenile Justice Board or by a court under Section 9. In POCSO cases, there is no similar authority to decide the age of the victim. For victims, any challenge to age-related documents must be decided during the trial. The Court referred to earlier rulings such as Abuzar Hossain v. State of West Bengal and Parag Bhati v. State of U.P. to support this view.

The Court also cited cases like P. Yuvaprakash v. State and Rajni v. State of U.P. to show that medical age tests are to be used only when primary documents are not available. These decisions make it clear that there is no rule requiring medical age tests to be done routinely at the very start of a POCSO investigation:

“The POCSO Act is one of the most solemn articulations of justice aimed at protecting the children of today and the leaders of tomorrow," observed the bench.” At the same time, the Court expressed concern about misuse of the Act through false age claims. However, it stressed that such concerns must be addressed through the procedure laid down by the legislature, and not by courts issuing broad directions beyond their legal powers.

Ruling:

Ultimately, the Supreme Court allowed the appeal, setting aside the Allahabad High Court's directions and also cancelled similar directions given in the Aman and Monish cases, holding that they were passed without proper legal authority and were not supported by the law.

The accused's bail stood, based on other merits and continued to operate, as it was based on other considerations. The Court also made its ruling prospective, so that earlier bail orders passed on the basis of those directions would not be affected.

The court directed that a copy of the judgment be forwarded to the Allahabad High Court's Registrar General for circulation.

Case Detail: THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH VERSUS ANURUDH & ANR

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts