Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

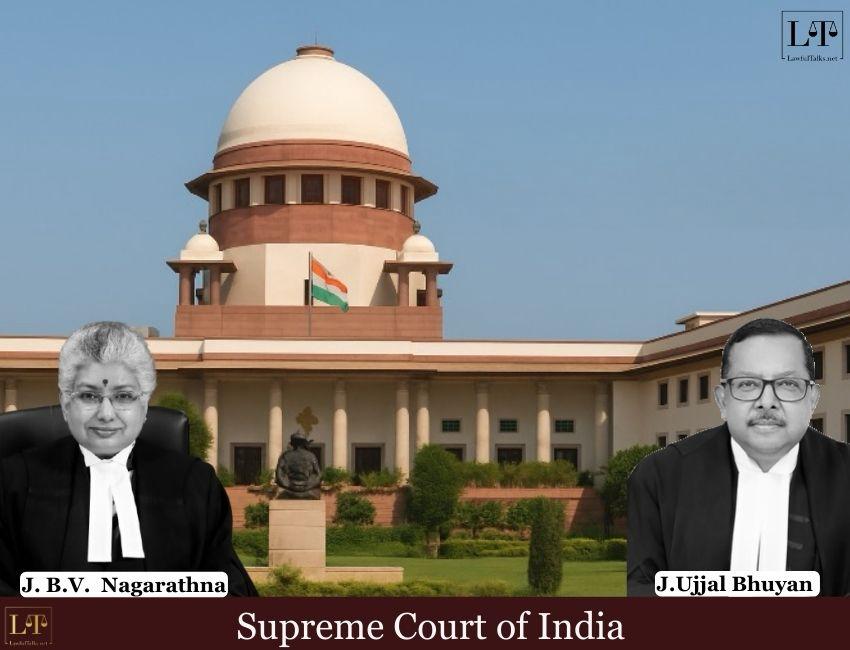

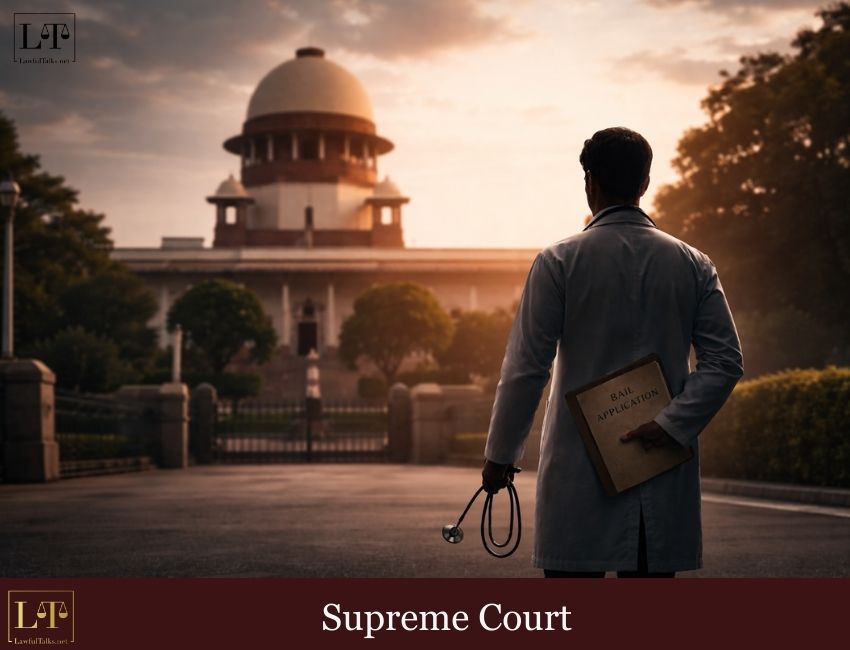

In a landmark judgment, Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice K.V. Viswanathan of the Supreme Court of India reinstated senior judicial officer Nirbhay Singh Suliya, who had been removed from service after 27 years of an unblemished career. The Court highlighted that judges should not face disciplinary action merely because their bail orders are seen as irregular.

Facts:

Nirbhay Singh Suliya began his judicial career on October 31, 1987, as a Civil Judge Junior Division in the Madhya Pradesh Judicial Service, rising through the ranks to become an Additional District Judge in 2003 and confirmed in that post by September 2008.

In May 2011, he was transferred to Khargone, District Mandaleshwar, Madhya Pradesh, serving as First Additional District Sessions Judge, where he handled various matters including bail applications under the Madhya Pradesh Excise Act, 1915.

Trouble arose when Jaipal Mehta, a local resident, filed a vague complaint with the Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court, alleging that Suliya was granting bail in Excise Act cases involving 50 bulk litres or more of liquor through his stenographer Anil Joshi in exchange for bribes, claiming Joshi boasted of influence over the judge and that similar complaints dated back to 1995-96.

The complaint did not mention any specific bail orders and made general allegations of corruption that harmed the image of the judiciary, which led the District Judge to order a preliminary inquiry and later start departmental proceedings.

The inquiry framed two charges against Suliya. The first charge alleged that he wrongly granted bail in four cases—dated August 1, 2011 (Lokesh vs. State), August 4, 2011 (Babulal & Ors. vs. State), December 7, 2011 (Mohan vs. State), and August 31, 2012 (Jitendra Nantiya and Gulab & Ors. vs. State). These cases involved seizures of more than 50 bulk litres of liquor, and it was alleged that bail was granted with corrupt intent and in violation of Section 59-A of the Excise Act, which lays down two mandatory conditions for granting bail.

This was compared with 14 other cases where he had refused bail and specifically referred to the same legal provision, which was cited as showing double standards and bad faith. It was also noted that one case listed as a bail grant was in fact a rejection, pointing to inconsistencies in the charges.

The second charge, involving a gang rape bail grant, was dropped as unproved. Suliya defended each order, noting reasons like challan filing, trial delays, applicants being local farmers with no flight risk, and reliance on precedents, even if Section 59-A was not explicitly cited in all.

During the inquiry, the complainant Jaipal Mehta was not examined. The department's witness, executive clerk Gendalal Chauhan, testified in favour of Suliya and said he had no knowledge of any corrupt dealings or influence peddling by Joshi.

A defence witness, Public Prosecutor K.P. Tripathi—who had appeared in all 18 related bail matters—supported the bail orders and stated: “In my opinion i.e. in the capacity of Public Prosecutor, the orders of granting bail were absolutely proper and on proper grounds.” He also said there were no double standards in the orders and that the State had not challenged them before higher courts.

Despite this evidence, the Inquiry Officer held Charge-I to be proved, concluding that Suliya had deliberately violated Section 59-A with oblique motives. As a result, Suliya was removed from service on September 2, 2014. This decision was upheld in appeal in March 2016 and later affirmed when his writ petition was dismissed in July 2024.

Supreme Court’s Analysis and Ruling:

The Supreme Court granted leave and examined the case in detail. Justice Viswanathan identified the main issue in these words: “The question before us is whether on facts, based on the four judicial orders of grant of bail per se and without anything more, the authorities were justified in removing the appellant from service?”

The Bench stressed the need to protect judicial independence and cautioned against frivolous complaints by unhappy litigants or members of the Bar, which could be used to harass or intimidate trial judges working under heavy pressure. As the Court observed, “A fearless judge is the bedrock of an independent judiciary.”

The judges said that strict action, including contempt proceedings or reference to the Bar Council, should be taken against those who make false accusations. At the same time, they directed that prompt action must be taken where misconduct is prima facie made out. Referring to earlier decisions, including Sadhna Chaudhary v. State of U.P. ,the Court clarified that mere errors, failure to mention a statutory provision, or different outcomes in bail orders cannot by themselves establish corruption, unless there is evidence of bribery, extraneous influence, or a tainted decision-making process.

The court closely examined the flaws in the inquiry. It noted that the complainant was never examined, the departmental witness supported Suliya, and the public prosecutor had endorsed the bail orders. The Court noted that the bail orders were supported by clear reasoning and were based on the right to personal liberty under Article 21. It further held that no bad faith could be inferred merely because Section 59-A(2) was not expressly referred to in the orders.

The judgment warned: “It will be a dangerous proposition to hold that judgments and orders which do not refer expressly to statutory provisions are per se dis-honest judgments.” Referring to earlier decisions such as K.K. Dhawan and R.R. Parekh, the Court reiterated that disciplinary action against a judge requires proof of recklessness, grant of undue favour, or corruption, and not simply an incorrect decision that can be corrected in appeal.

The Court held that the findings of the inquiry were perverse, observing that “no reasonable person would have reached the conclusion that enquiry officer reached.”

Justice Pardiwala concurred with the decision and praised the main judgment as “ineffable” for protecting district judges from being punished simply for how they grant or refuse bail, which otherwise increases the burden on higher courts.

He cited the maxim “Nemo Firut Repente Turpissimus” (no one becomes dishonest all of a sudden) and pointed to Suliya’s clean service record. He said that a judge’s integrity cannot be doubted on suspicion or guesswork, but must be judged on clear probability.

The appeal was allowed. The orders removing Suliya from service and the High Court’s decision were set aside. Suliya was treated as having remained in service until retirement and was granted full back wages with 6% interest, to be paid within eight weeks.

The judgment was circulated to all High Court Registrar Generals to safeguard honest judicial officers.

Case Detail: Nirbhay Singh Suliya v. State of Madhya Pradesh and Anr. SLP(C) No. 24570/2024

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts