Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

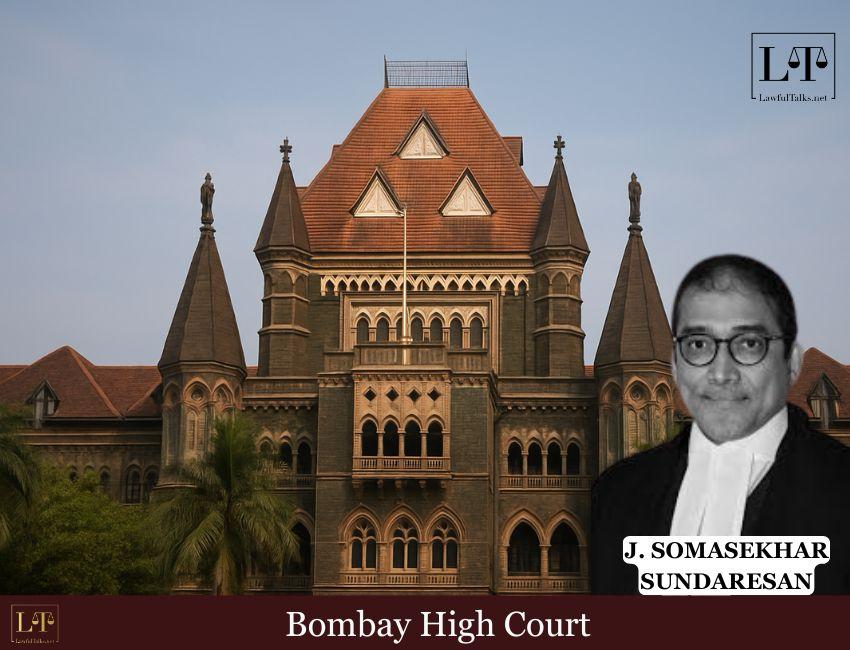

In a landmark ruling, Justice Somasekhar Sundaresan of the Bombay High Court, examined whether the court, while exercising its extraordinary powers under Article 226 of the Constitution, can order a refund of stamp duty paid on an agreement for sale that was never executed. The ruling makes it clear that, in suitable cases, fairness can be given priority over rigid procedural rules under the Maharashtra Stamp Act.

Facts:

The case concerns Suresh Ramchandra Sancheti, who is the legal guardian of his wife, Sunita Suresh Sancheti. Sunita suffered an aneurysmal stroke in 2017, which left her with 100% locomotor and mental disability, and Suresh was formally appointed as her guardian in 2019.

In July 2019, Suresh entered into an agreement to buy a neighbouring flat for Rs. 1.80 crores. On July 6, 2019, he paid stamp duty of Rs. 10.80 lakhs through electronic payment via Punjab National Bank, along with a registration fee of Rs. 30,000, and received the required challan and certificate. A draft agreement for sale was prepared, but it was never signed or executed.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the family decided not to go ahead with the purchase so that they could focus on Sunita’s medical care. As a result, the stamp duty already paid could not be used. Suresh applied for a refund on September 15, 2020, under Section 47(b) read with Section 48(3) of the Maharashtra Stamp Act, 1958, stating that the document had been written but not signed.

The Additional Controller of Stamps rejected the refund beyond six months from the date of purchase of the stamps. This decision was later upheld by the Inspector General of Registration on October 4, 2022.

Court’s Observations:

Justice Sundaresan carefully explained how the Maharashtra Stamp Act works. He noted that under Section 3, stamp duty is levied only on “instruments”, which are defined in Section 2(l) as documents that create, transfer, limit, extend, extinguish, or record rights or liabilities. Under Section 17, this duty becomes payable at the time the instrument is executed. As the Court observed, “Stamp Duty is not a transaction tax but a duty payable on an instrument, which necessarily has to conform to the definition set out in the Act.”

He further clarified that an instrument comes into existence only when it is executed, and execution, under Section 2(i), means signing the document. Since the agreement in this case was never signed, no instrument ever came into existence, and therefore no stamp duty was legally chargeable. In this context, the Court explained that the word “document” used in Section 47(b) is different from the words “instrument” in Section 47(c) and “paper” in Section 47(a), and that each term has a separate meaning under the law.

The court also explained that the electronic payment of stamp duty resulted only in a receipt, and not a Collector’s certificate as contemplated under the Explanation to Section 32. However, the payment still amounted to a valid stamp payment that had become spoiled and useless because the agreement was never executed.

For such cases, Section 48(3) requires a refund application to be made within six months from the date of purchase of the stamp. In Suresh’s case, this deadline was missed by more than a year.

The Court closely examined Section 47 of the Stamp Act, which provides for refunds in different situations where stamps are spoiled, such as when a document is never executed or when an instrument turns out to be void. It also considered Section 48, which sets time limits for seeking such refunds—six months from execution in cases covered by Section 48(1), and six months from the date of purchase of the stamp in cases covered by Section 48(3).

Although the authorities were technically right in rejecting the refund application because it was filed late, Justice Sundaresan held that Section 48 only lays down a procedure and does not take away the substantive right to a refund given under Section 47.

As he clearly stated, “The substantive right to allowance for Stamp Duty is in Section 47 of the Stamp Act while the procedural deadline for the application for allowance to be made is stipulated in Section 48 of the Stamp Act.”

The Judge also noted that other provisions of the Act, such as Sections 49, 50, and 52, allow refunds either without any time limit or with different time limits. For this reason, he rejected the State’s attempt to keep stamp duty paid on documents that were never executed, holding that the law does not permit the State to profit in such cases.

Relying on earlier decisions, the bench examined several important rulings of the Supreme Court and the Bombay High Court. He referred to the Committee of GFIL v. Libra Buildtech (2015) 16 SCC 31, where the Supreme Court directed a refund of stamp duty even though the application was delayed, after the transaction was reversed following execution.

In that case, the Court applied the principle “actus curiae neminem gravabit” (an act of the court should prejudice no one) and quoted the well-known observation of Chief Justice Chagla : “when the State deals with a citizen it should not ordinarily rely on technicalities, and if the State is satisfied that the case of the citizen is a just one… it must act… as an honest person.”

The Judge also noted Rajeev Nohwar v. Chief Controlling Revenue Authority (2021) 13 SCC 754, where the Supreme Court used its powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to order a refund of stamp duty. He referred to Satish Buba Shetty (2024) 3 Mh LJ 293, in which the Bombay High Court granted similar relief by exercising its writ jurisdiction under Article 226.

Further, in S.K. Realtors (2016 SCC OnLine Bom 14536), the Court had held that the State cannot enrich itself by retaining stamp duty paid on documents that were never executed, even in cases involving franking. The Judge also relied on Harshit Harish Jain (2025) 3 SCC 365, where the Supreme Court emphasized that “a mere technical delay should not, by itself, extinguish an otherwise valid claim,” and clarified that the law of limitation bars the remedy, not the right itself.

Justice Sundaresan noted that, unlike many earlier cases where documents were signed and later cancelled, no instrument was ever created in the present case. He observed that this fact, along with the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and Sunita’s severe disability, made the case for relief on equitable grounds even stronger.

Justice Sundaresan held that interference under writ jurisdiction was justified because keeping Rs. 10.80 lakhs would amount to the State being unjustly enriched from an “unborn instrument that had been aborted.” He clearly stated that “The stamp duty being retained by the State would constitute unjust enrichment and would result in an unfair and unjust outcome for Suresh and Sunita.”

The Court explained that while statutory deadlines bind the stamp authorities, they do not restrict the High Court when it exercises its powers under Article 226 to ensure substantive justice.

Order:

Accordingly, the writ petition was allowed. The impugned orders were set aside, and the authorities were directed to refund the stamp duty amount within six weeks from the date the judgment is uploaded, with interest to be processed as per the applicable rules. The rule was made absolute, with no order as to costs.

Case Details: Suresh Ramchandra Sancheti v. State of Maharashtra.

Appearance :

Advocate For the Petitioners: S. R. Nargolkar a/w Arjun Kadam & Neeta Patil, Advocates.

Advocate For the Respondent: Y. D. Patil, AGP

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts