Allahabad HC Sets Aside Afzal Ansari's Conviction, Allows Him to Continue as MP

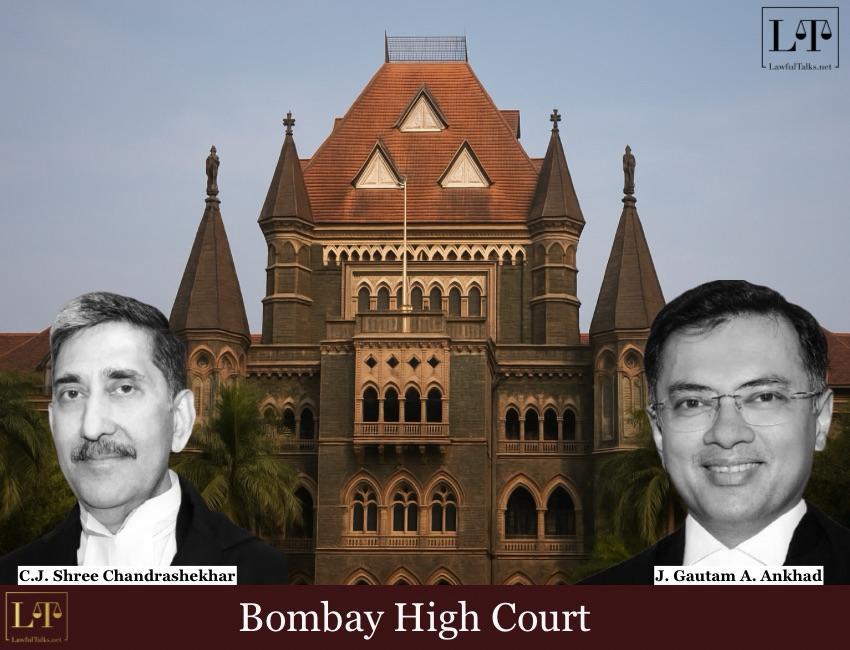

What began as a landmark transparency initiative at the Bombay High Court has quietly receded. Months after live-streaming of proceedings was rolled out with high expectations, public access has been switched off in several key courtrooms. Among the courts that have disabled public access are the Chief Justice’s bench and a few other benches, even as the live-streaming infrastructure remains fully operational.

The initiative drew inspiration from the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling in Swapnil Tripathi v Supreme Court of India, which encouraged courts to open their proceedings to the public through digital access to enhance transparency. In that case, former Chief Justice of India, Dr. Chandrachud held that live streaming of court proceedings is supported by Article 21, which guarantees the right to access justice, and Article 145(4), which requires judgments to be pronounced in open court.

However, the Bombay High Court’s initiative has been scaled back as judges grew wary of courtroom videos being edited and circulated on social media, leading to public backlash.

A major controversy arose after a viral video—allegedly edited by a lawyer’s father—showed a judge of the Bombay High Court asking a young woman advocate to leave the courtroom. The video increased frustration within the judiciary and led to restrictions on public viewing, rather than action against those who shared the clip.

Although court websites still show links for live streaming, viewers now see just a clear message: “Public viewing of the proceedings has been disabled by the Court.”

A senior official explained, “the hardware is fine. It’s only the public link that’s switched off.” The infrastructure, built using existing video-conferencing systems with additional cameras and links, is still ready for virtual hearings. “The system remains functional and can be activated at a moment’s notice,” the official added.

At present, only advocates-on-record can access the secure live feeds. Litigants, journalists, and the general public are excluded, and the website gives no public explanation for this change.

The live-streaming initiative was launched in the Bombay High Court in July 2025 by then Chief Justice Alok Aradhe, with five benches to begin with, under the 2023 Live Streaming Rules. These rules allow court proceedings to be broadcast with the consent of the presiding judges, but sensitive matters such as matrimonial disputes and POCSO cases were excluded.

The rules prohibit recording or sharing clips without permission and warn of action for contempt of court, violations under the IT Act, or copyright breaches. Despite this, edited and out-of-context videos made judges less supportive of live streaming.

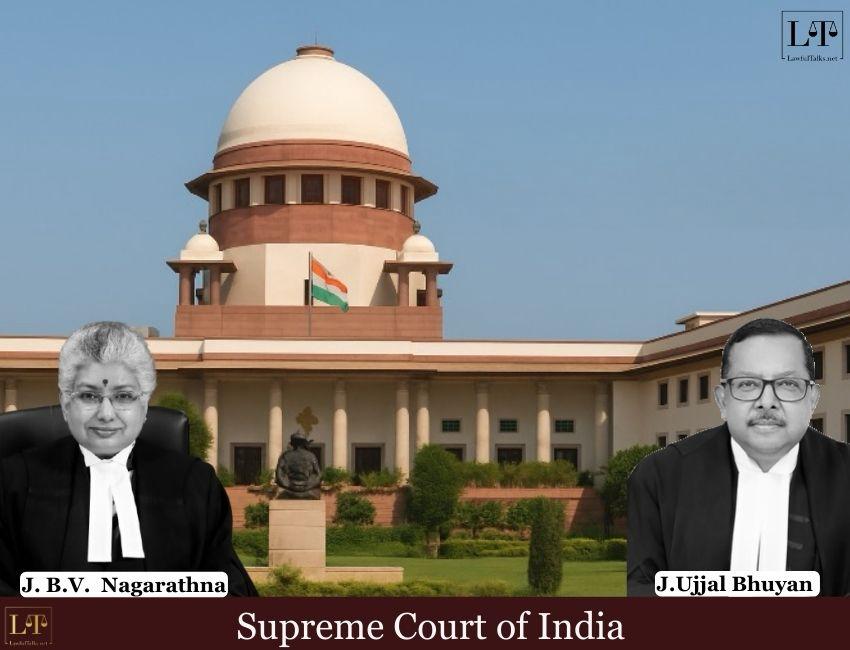

This concern was reflected in August 2025, when Justices AS Gadkari and Rajesh Patil warned that streaming cases involving crimes against women could compromise victim privacy.

Former Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai, who inaugurated the live-streaming facility, raised concerns about the misuse of edited clips and called for clear national guidelines.

Live streaming practices differ across courts in India: the Supreme Court regularly streams constitutional cases, while High Courts in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Calcutta, and Karnataka provide proceedings through YouTube.

Retired Supreme Court judge , Justice Abhay Oka has strongly supported live streaming, saying it helps the public understand how courts really function:

“Live-streaming is primarily about transparency in the decision-making process and about letting the public, especially students and researchers, see advocacy and judging as it actually unfolds.”

He added that judges are often cautious because social media tends to share only brief, sharp, or critical moments from court hearings, even though such exchanges may later be followed by decisions in favour of the same party.

“When only those sharp exchanges are clipped and circulated, people can misunderstand the process of the court,” he said.

He also stressed that, "The governing principle is simple. Any case that significantly implicates an individual's right to privacy under Article 21 should be kept outside live streaming by default”.

At the same time, he played down fears of misuse, pointing out that such recordings existed even before live streaming. “The difference now is that social media gives such recordings a wider audience,” he added.

“What Are We Afraid Of?”: Questions on Restricted Access

Bar members are pressing for the revival of live streaming, along with access to live transcripts. Senior Advocate Jamshed Mistry questioned why access is restricted, asking, “Whether they are lawyer, litigant, media or even judicial officers, why are they not allowed to view? What are we afraid of? The courts are open. If there are sensitive issues, there are safeguards to it.”

He added that this would be especially useful for students, noting, “You can play court proceedings in classrooms without disrupting court proceedings.”

Pointing to live streaming in Calcutta and Gujarat High Courts, as well as in countries such as Jamaica and Pakistan, Mistry added, “Having transcripts published will in fact make reporting accurate.”

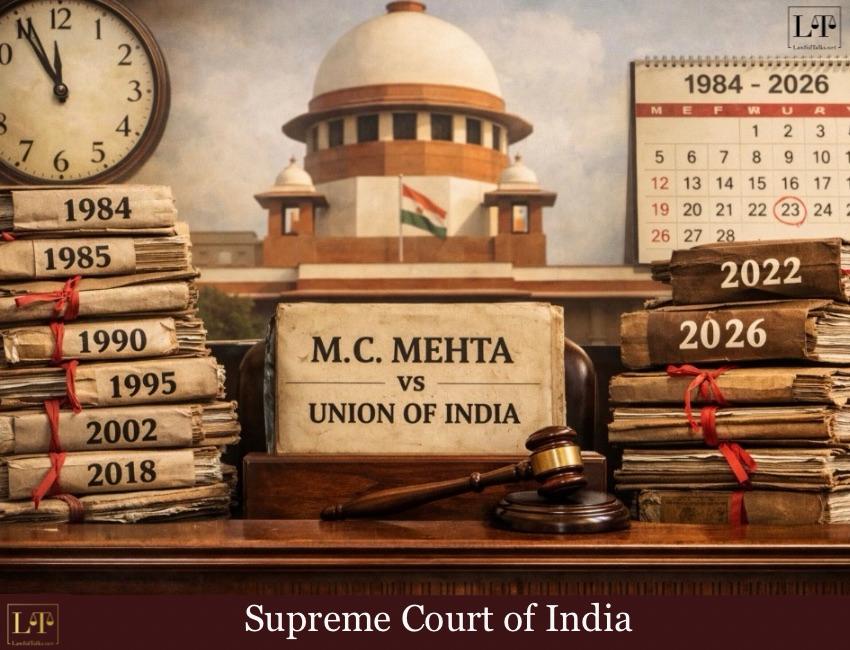

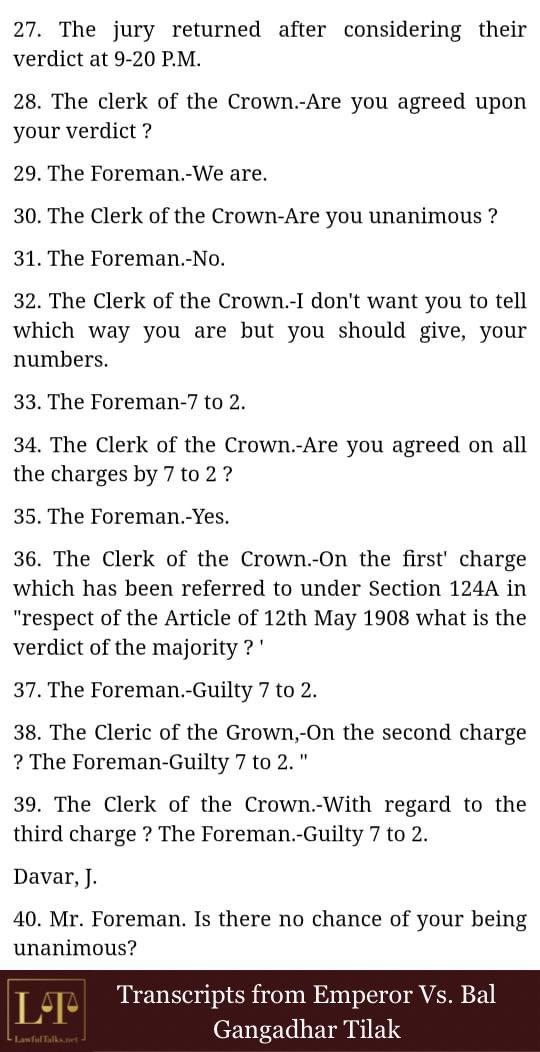

Mistry expressed the view that both transcripts and footage should be made available. He said that if judgments and transcripts from the 1908 Emperor v. Bal Gangadhar Tilak case are still available today, there is no justification for denying the same level of record-keeping and public access in the present day.

This position finds resonance in senior advocate Indira Jaising’s public statement that,“One milestone achieved, now we must ensure the Supreme Court has its own channel for a permanent record, until then use YouTube, and we must preserve the transcripts of court records as so ably argued by @jamshedmistry,” She highlighted that lasting official archives and preserved transcripts are important alongside live streaming.

Mistry added, "Having transcripts published will in fact make reporting accurate,"suggesting that clear records could reduce misreporting and misunderstanding of court proceedings.

Learning From History:

He has also furnished the transcript of the 1908 decision in Emperor v. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, thereby demonstrating that detailed records of courtroom proceedings were being prepared and preserved even at that time.

Technical Hurdles In Practice:

However, despite this historical precedent, practical glitches continue to trouble lawyers today. Advocates often report problems such as mismatched platforms (Zoom vs. vConsol), audio-video inconsistencies, and delayed access that can lead to missed calls. They said that in some benches, viewers can hear the judges but not see them, while in others, live streaming is completely shut. Some have suggested using OTP links for traceable litigant access, while others, speaking on condition of anonymity, acknowledge that streaming is not a right and depends on consent.

At present, only eight principal-seat benches and regional ones in Goa, Nagpur, Aurangabad, and Kolhapur offer limited live streaming, even as much of the installed hardware remains unused because most hearings happen in person.

While judges’ fears about social media misreporting, out-of-context clips, edited live streams, and public backlash are neither unreal nor unfounded-and notwithstanding advocates’ reports of technical glitches- the Bombay High Court’s commitment to openness and transparency must still be upheld.

As other courts adapt to digital change, the Bombay High Court finds itself at a crossroads, still grappling with how to balance judicial caution with its promise of openness.

Anam Sayyed

4th Year, Law Student

Latest Posts

Categories

- International News 19 Posts

- Supreme Court 390 Posts

- High Courts 383 Posts